FEEDBACK

Welcome to Superyacht FEEDBACK

Welcome to the first edition of Superyacht FEEDBACK! This is a new editorial that complements our established but more general Maritime FEEDBACK newsletter which covers the entire maritime industry. Firstly, we want to say a huge ‘thank you’ to those of you who asked us to produce a separate and distinctive publication with particular focus on safety issues encountered on board superyachts. We hope that we’ve met your expectations – let us know either way!

And thank you to everyone who submitted safety reports to us, either through our website reporting portal or via our app. We recognise that reporting can often be a difficult step, but we rely on your reports to raise awareness of safety issues, and you really are helping to improve safety outcomes by doing so; so thank you.

We believe that our safety newsletters differ to many others because we focus on the primary human-factors that contributed to incidents and near misses. These are listed at the end of each report for ease of reference and to stimulate conversations about safety. CHIRP believes in a ‘just’ reporting culture, so while we may highlight failures of process and procedure, we never ‘name or shame’ and go to great lengths to ensure that individual people, ports or vessels cannot be identified.

We hope you find this an interesting and informative read, and please do let us know your thoughts (both good and bad) so that we can make future editions even better. And do please keep your reports coming!

Yours in safety,

The CHIRP Maritime team

-

M2084

–

Entrapment in running equipment causes serious personal injuryEntrapment in running equipment causes serious personal injuryInitial Report

“On the dock, pulling on the running backstay requires someone pulling the block forward to keep lines off the teak deck. The supervising officer operated the winch at high speed, and the crew member on the block got their hand caught in it. As the block lifted, it hoisted the crew member roughly 5m high. It suddenly stopped, catapulting the crew back to the deck, missing the mainsheet track by 10cm. The casualty suffered a broken wrist, required stitches to the lip and chin, and was knocked unconscious for 5 minutes. The crew member had to pay for their flights home and was off work for a month.”

CHIRP Comment

There needed to be better coordination between the supervising officer and the person working the block. Clear verbal warnings that the hoist was about to start would have alerted the crew member to keep their hands clear. The use of closed-loop communications in such circumstances should be considered, e.g., the crew person responding “Clear!” to the officer’s alert of “Operating winch!” or similar.

Large super yachts are fitted with powerful equipment items, and understanding their power must be part of the familiarisation process for all crew. CHIRP also asks whether the crew person was even needed. If the concern was that the block might scratch the teak deck, wouldn’t a canvas cover or other covering have sufficed?

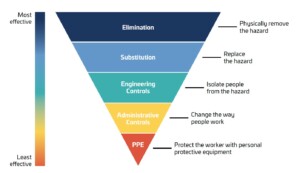

Use the hierarchy of controls diagram-eliminate the hazard.

Toolbox talks are not standard in the super yacht sector of this industry, but CHIRP recommends adopting them, including Stop Work authority.

CHIRP feels the owners have a duty of care to look after and support the injured crew until they fully recover.

Key Issues relating to this report

Communications: Use closed-loop communications for safety-critical evolutions such as lifting.

Teamwork: Better coordination between the winchman and the block handler would have reduced the risk of entrapment.

Local practices: Where possible, reduce entrapment risks by looking for alternative methods to achieve the aim. A floor covering would have been a safer option.

Culture: The report that the casualty had to pay to repatriate themselves suggests poor personnel and welfare standards on board, which is also an indicator of a poor safety culture.

This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help. -

M2083

–

Tender groundingTender groundingInitial Report

“I was asked to take guests on a sunset cruise on a jet drive tender around the island in the South Pacific. I warned the captain that multiple shallow spots on the main yacht’s ECDIS were not shown on the Tenders. I was told to try, so we set off but halfway around the island, and as the sun went down, it became harder to see the unlit posts, which indicated the safe routes around the reef.

I decided to turn around, and on the return trip, we missed one post, and the tender went aground on a reef and could not refloat as the tender as the tide was dropping. We had no radio or phone signal, but a passing local fisher gave us a lift back to the yacht, and we returned with the fisher on the high tide that night to recover the tender.”

CHIRP Comment

The captain intentionally deviated from safety procedures in directing the tender trip to go ahead despite knowing that the charts were inadequate for safe navigation, particularly at night. This placed the reporter in a difficult ‘no win’ position: either to disobey their captain or undertake a trip against the rules of good seamanship. The reporter did challenge the captain, but the captain prioritised the guests’ wishes ahead of theirs and the crew’s safety which suggests

a poor safety culture on board. It also means poor planning – had the trip been organised more thoroughly in advance, the inadequacy of the charts would have become known sooner, and an alternative route away from the reefs might have been possible, or the course reconnoitred by day and saved into the tender’s ECDIS. The Master’s standing orders should state that no tender should leave the mother ship without adequate communications equipment.Similarly, a comprehensive risk assessment would have identified that VHF coverage would have been inadequate once out of sight of the parent vessel. A patchy phone signal should always be expected in remote areas.

Key Issues relating to this report

Culture: The captain’s order to launch with inadequate charts was a safety violation.

Pressure: the authority gradient between the captain and reporter meant that the latter probably couldn’t refuse the order. Putting guests’ wishes before their safety indicates that the captain had not developed a good working relationship with the guests. A formal brief upon their arrival that “safety supersedes everything else” would have prevented the captain from putting themself under pressure to accede to the guests’ wishes.

Teamwork/Planning: a thorough risk assessment, a better route choice, or a prior recce would all have prevented this incident.

Communications: When working remotely, assume that communications will be difficult. Does your vessel have a ‘tender overdue’ procedure? A tracking device fitted on the tender should be considered.

This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help. -

M2085

–

Lack of familiarity with equipment puts the vessel in dangerLack of familiarity with equipment puts the vessel in dangerInitial Report

Our reporter served on a >500 GT yacht as part of a newly assembled crew. They were employed to take the vessel out of the dry dock and sail to the delivery destination. During the passage, an off-duty officer went onto the bridge and noticed a crossing vessel on the starboard bow. The officer on watch was asked if they were going to take action. The officer responded, ‘Yes, using the autopilot. The off-duty officer advised that the vessel was too close to use the autopilot and that the manoeuvre should be made using hand steering. The officer of the watch appeared to struggle to make the change over to engage hand steering and was quickly assisted by the off-duty officer to make the change over to hand steering and take avoiding action.

CHIRP Comment

An officer must only take over a watch if they are fully aware of the functions of the bridge equipment. Familiarity with equipment, particularly that essential to safely control the ship, must be undertaken during initial familiarisation training.

If not sure, always ask for clarification. There is a lot to take in when being familiarised on joining, and some operations for the equipment can be complicated and

quickly forgotten.Key Issues relating to this report

Capability: The OOW was unfamiliar with the steering controls and would be considered not competent in the use of this equipment.

Teamwork: Good teamwork relies on knowing the strengths and weaknesses of yourself and your team members. In this case, the duty officer had not requested any support, probably through fear of looking incompetent.

Culture: When assembling a new team, especially on a short-term contract where everything and everyone is new to the team, it is essential to develop a safety culture. This is best achieved through basic emergency exercises, confirming that the emergency systems work as expected. The master is responsible for ensuring that all officers and crew can respond to emergencies and support each other.

This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help. -

M2086

–

Dangerous recovery of a person in the waterDangerous recovery of a person in the waterInitial Report

During tender training in port, while making an approach, the helm discovered that the controls did not respond as expected because the throttle actuator had broken. The helm applied astern propulsion to slow the tender; this resulted in greater forward motion. The tender inevitably collided with another moored vessel, and the force of the impact threw the training officer into the water. They recovered themselves back into the tender by climbing up the stern drive props, which could have caused the trainer serious injury.

CHIRP Comment

Although the trainer was undoubtedly in shock having been thrown overboard, the decision to get back onboard by climbing up the stern propulsion system was exceptionally dangerous, particularly given that the actuator had failed. The helm that remained on board should have directed the trainer away from the stern to get back on board the tender from the side of the tender using a recovery ladder.

Key Issues relating to this report

Situational Awareness: Situational awareness can be seriously affected when stress is high. While getting back on board, the tender may have been more accessible via the stern drive props; it was the most dangerous access point.

Pressure: Under time pressure to get out of the water, the training officer chose the most dangerous option to climb out. Even when the engine is in neutral, propellors can sometimes turn sufficiently fast to cause significant trauma.

Complacency: Before making an approach, it is advisable to check that the control systems and steering are functioning as expected. The tender’s controls should

always be tested at the commencement of any operation and verified as functioning.This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help. -

M2088

–

Pressurised to make a fatal decisionPressurised to make a fatal decisionInitial Report

The superyacht was anchored in a bay where jet skis had been prohibited due to the density of traffic in the anchorage and a spate of previous incidents.

The owner was on board with a fellow guest who drank heavily. They requested that the jet ski be launched. The captain explained that using jet skis was prohibited and ill-advised when inebriated. The owner and his guest were insistent, and this conversation escalated until the captain was given the ultimatum of either launching the jet-ski or being dismissed.

The captain yielded to this threat, and the jet ski launched. Shortly after, the owner’s guest had a high-speed collision with a nearby vessel. The casualty was recovered from the water, unconscious and severely injured; the crew found he was not breathing and commenced CPR, but the casualty died before emergency services arrived.

The result was one death, a traumatised crew and owner, and the captain losing his job. He remained out of work for the following two years while under investigation and threat of criminal prosecution.

Superyacht owners are often demanding and “no” is unfamiliar to them and seen as an insult. Captains who stand their ground risk being side-lined for their professional conduct, and those that do yield to such demands potentially face even more dire consequences.

CHIRP Comment

The drink had clouded the judgement of the guest and the owner, but the captain knew that jet-skiing in the bay was prohibited. Even if the owner had sacked the captain on the spot, once they had sobered up, they would most likely have realised that the captain was speaking objectively, not subjectively. However, even when it could place others in danger, it can still be hard to refuse a request or order by an owner, particularly if they are used to getting their way or see refusal as a challenge to their authority. In this instance, the owner bullied the captain into launching the jet ski against their professional judgement. However, a captain’s

first duty is the safety of crew and passengers, and they should have refused, no matter the circumstances.To avoid such scenarios, captains are encouraged to confirm with the vessel’s owner that they are empowered to refuse requests that put people or the vessel at risk of harm – and, crucially, that they will be listened to. Ideally, this should be done as early in the professional relationship as possible – potentially even at the interview. Shrewd owners will accept that the captain is looking after their interests. Where such assurances are not forthcoming, this should be a ‘red flag’ to

the captain that safety on board is at some point likely to be compromised. Better to seek alternative employment at that point than find oneself being threatened with the sack in the heat of the moment. CHIRP wants to state that the master has other places to report this coercion, which should be made known to the master.Key Issues relating to this report

Fit for duty: Drink had impaired the judgement of both the guest and the owner.

Pressure/culture: The owner bullied the captain into going against their professional judgement. On board, such behaviour was reflected in the safety culture (and probably the welfare culture).

Yacht crew can contact the International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN) via WhatsApp (+44 (0)7514 500153) for 24-hour help and support for issues such as bullying and harassment, unpaid wages, and mental health support.

This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help.