FEEDBACK

Report by report we can make aviation a safer place.

What do you do when something goes wrong onboard that relates to safety?

We all know what should happen; the event (or close call) should be reported internally as soon as you can do so. Sadly, all too often people feel that once the matter has been ‘sorted’ there’s no need to report and so it goes unreported. In the end, this means that important lessons are then not learned by your fellow crew and SOPs can’t be changed (if required) by your company.

Submitting a safety-related report about incidents can be scary, and there are plenty of rational reasons to be worried about doing it. As ex-cabin crew, pilots, engineers, and ground handlers ourselves, we know all about those fears at CHIRP, the Confidential Human-Factors Incident Reporting Programme. Those fears are known as the ‘four Rs’: revealing your identity, reprisals from managers, ridicule for speaking out, and rejection if your reports are ignored or suppressed. That’s why, over 40 years ago, CHIRP was founded and there are many other confidential reporting schemes worldwide (and outside of aviation) based on CHIRP. We are the UK’s only confidential, independent and impartial aviation safety reporting programme and across thousands of reports (some of which have shaped company or regulatory policy) we have never revealed a source.

Protecting you and your safety

As anyone with experience of working in aviation will know, a lot has changed in those 40 years. New ways of working onboard and commercial demands – as well as new technologies – have changed the industry, mainly for the better. One thing that has not changed is the need to continuously improve safety. At CHIRP Aviation we work hard to ensure that cabin crew, pilots, air traffic controllers, ground handlers and engineers can report safety-related incidents and near-misses easily and without risk to them or their job. Reports from other aviation communities, including General Aviation (light aircraft, gliders, skydiving, etc.) and Drone/UAS (pilots and operators) are also welcomed by CHIRP Aviation.

By sharing information with us, we may identify safety issues in the aviation industry so that others can learn from them and prevent such events in the future. Knowledge is power and the more reports received the more lessons can be shared. If we see safety trends being repeated across the Industry, we are able to share these with operators and regulators. We want to empower cabin crew; by allowing us to amplify your voice. By submitting a report you are helping to raise safety standards across the wider aviation industry for everyone.

The ‘how’ and ‘why’

While CHIRP is a safeguard for crew worried about the risk of speaking out, reporting to CHIRP does not replace official company reporting channels, it is often a requirement within an Operations Manual to report safety events within their Safety Management System (SMS). The most immediate way of making a difference to the safety of crew and passengers is for your company to be made aware of not only actual incidents but also near misses. However, if you feel unable to report internally, submitting a report to CHIRP ensures that those learnings are anonymised.

Reporting to CHIRP is simple, you can submit a report online or via our app in minutes. Anything that could be used to identify a reporter is removed by us and we liaise with the reporter (you!) every step of the process. Managers and colleagues will never know who has made a report.

The CHIRP cabin crew programme receives hundreds of reports a year, not all of them need actioning, however, the data from those reports helps the industry monitor trends and highlight areas that may be of concern. Our tri-annual newsletter features some of your reports, these reports allow our readers to learn from your experience and help to prevent the same incidents from recurring again. Some of these reports are also shared via our social media platforms, help us share our safety message by following us on Facebook, X, and LinkedIn

Improving industry-wide safety together

Recent reports have highlighted a range of concerns including commercial pressures and fatigue. Sometimes the reports lead to changes in company policy and, where needed, to intervention by the regulator.

Each report plays its part in raising awareness of important safety issues, wider trends and provides lessons for crew and aviation leaders alike to learn from. To make sure your colleagues have the opportunity to learn from your safety experiences, and to make the aviation industry a safer place to work, trust CHIRP. Report by report we can make aviation a safer place.

Stay safe,

Jennifer Curran

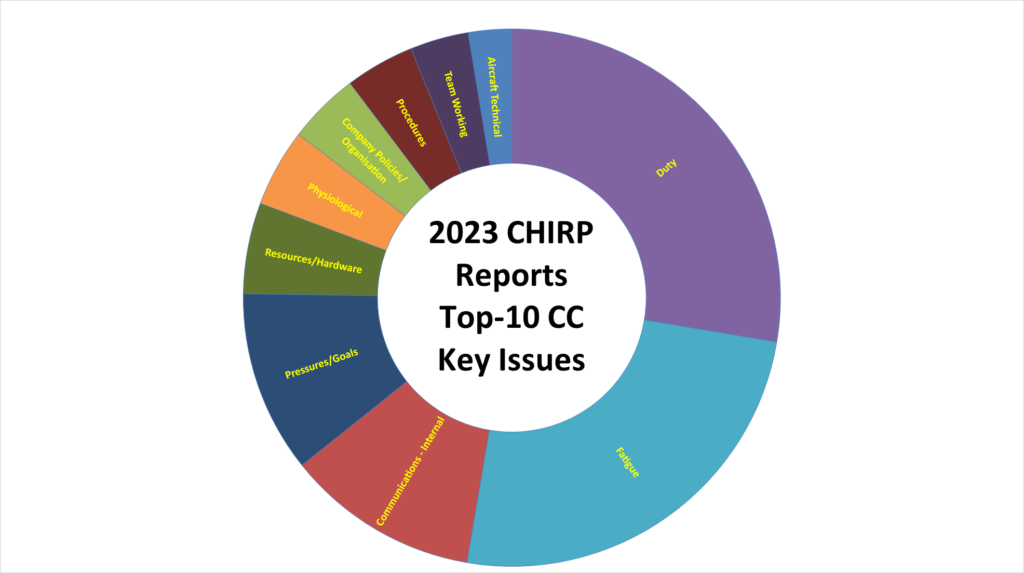

Cabin crew, primarily from UK operators, have submitted confidential safety-related reports on a variety of topics to CHIRP. The top-2 key issues for 2023 were related to duty periods and fatigue. The 3rd highest key issue related to internal communications which includes reports related to communications with management, scheduling teams, crew to crew and safety notices. The Top-10 Key issues are shown in the accompanying graphic:

CHIRP would like to express its gratitude to Lisa Huttlestone, who due to starting a new role away from cabin safety has stood down from her position as Chair of the CHIRP Cabin Crew Advisory Board (CCAB). We are immensely grateful for Lisa’s contribution throughout the years, both as a CCAB member and, from June 2019, as the Chair of the CCAB.

We value your opinion about our FEEDBACK newsletters and associated engagement methods, please spend a few minutes responding to 10 short questions about CHIRP Aviation FEEDBACK.

The CHIRP Aviation Programme also provides a facility for confidential reporting of Bullying, Harassment, Discrimination and Victimisation (BHDV) where there is an identifiable safety-related concern. CHIRP has no specific expertise or resources to investigate BHDV reports. CHIRP’s role is to aggregate data to build a picture of the prevalence of BHDV in the aviation sector. See our BHDV page on the CHIRP website for further information. CHIRP’s role in reporting Bullying, Harassment, Discrimination and Victimisation (BHDV)

Jennifer Curran

Cabin Crew Programme Manager

-

CC6328

–

Cabin crew trainingCabin crew trainingInitial Report

I have genuine concerns about some crew members’ knowledge when it comes to training. Mainly for recurrent training. We use a system of revision banks, which is essentially a bank of questions that everyone has access to and enables them to revise from. When it comes to the exam on recurrent training a selection of questions are pulled from these revision banks for the exam. So in theory they’ve gone through every single question in the bank of questions beforehand and when it comes to the classroom it’s a case of picking out the right word that stands out. This then promotes a culture of using said revision banks to revise from and not the necessary manuals to execute the job confidently as there is no incentive to read the manual when people can use revision banks which are the actual exams. This then in turn creates the wrong learning culture. Granted, it is a refresher. But it seems to have gone from a regimented environment of reading the manual and writing/drills/location diagrams etc to a free-for-all on a multi-choice exam to which everyone has access to. I’m not saying it needs to be how it was, but it’s gone too far the other way where now people don’t attempt to read the SEP manual and use revision banks as the main point of revision and then generally people achieve 100% in exams due to this.

When crew do fail, it is even more concerning when they have had access to revision materials such as revision banks beforehand and still fail. Perhaps revision banks are acceptable but not to replicate the actual exam papers and select a random amount/selection from such aids? People become so focussed on them which cover a small amount of the associated manuals but not refreshing on all knowledge. It almost seems like a quick fix and people revise in this way without actually retaining the information because they just look for the right word or keyline in the choice of answers. This then begs the question that if something were to happen onboard what would they do?

CHIRP Comment

A crew member has the responsibility of maintaining their knowledge base which should be updated regularly rather than just once a year when preparing for Recurrent training. Crew members undergo evaluations all year round during pre-flight briefings, line checks, and/or onboard assessments. Assessments during recurrent training go beyond the formal test, over these two or three days there will be several opportunities for learning and evaluation, as well as practical equipment handling, competency-based training, and/or scenarios.

-

CC6466

–

Neurodiverse CrewNeurodiverse CrewInitial Report

There has been an influx of new crew and many of them are posting on social media that they have ADHD and saying their symptoms make their role difficult e.g. can only work one position, can’t concentrate, short attention span, and are easily distracted, are unable to listen or carry out instructions, can’t organise tasks, have little or no sense of danger.

They openly admit that this wasn’t disclosed at their medical.

I am concerned that an ADHD diagnosis is not compatible with a safety critical role and how they would perform in an emergency.

Company CommentSince the pandemic the business was subject to a reorganisation. As a result, the Occupational Health function has been outsourced and the recruitment process simplified which may have contributed to some incidents regards to neurodiversity.

A number of steps have been taken as below to prevent reoccurrence:

- For future training courses, delegates will be sent a link with a declaration to say they do/do not have reasonable adjustments to declare.

- This will be reviewed and see if any support is required. Any concerns will trigger a formal review including an Occupational Health referral.

- A company neurodiversity policy is being written as we write which will cover ‘safety critical roles’ such as cabin crew.

- If crew fail to disclose neurodiversity and this is later discovered an Occupational Health referral will be required and a review by the line manager.

Some challenges experienced with neurodiversity subject:

- The regulator does not provide guidance on neurodiversity for the recruitment of cabin crew

- Neurodiversity conditions are on a spectrum which normally require individual assessment around safety related behaviours

Employment law would have a part to play in the form of the Equality Act (2010). If ‘reasonable adjustments’ cannot be made/those adjustments are incompatible with the role/or the safety concerns are so significant then the operator has the ability to manage the behaviours from a safety angle and if required, terminate the employment contract.

Our organisation spent a considerable amount of time and effort giving people every opportunity from point of application to declare, confidentially any condition that they have that might require support and adjustment. When this does not happen, it will be for crew management to address following an occurrence report

CAA CommentThe assessment of cabin crew fitness is carried out by Aeromedical examiners or occupational physicians appointed by the Authority. These individuals have the requisite knowledge of this safety critical role to make appropriate decisions on fitness. This includes experience in assessing individuals with neurodiversity, the spectrum of which is broad. Individuals must declare medical conditions to their examiner and this is part of their obligation to maintain the safety of flight.

CHIRP Comment

Most organisations have strict policies regarding the appropriate use of social media and any safety-related concerns raised on these platforms should be reported internally.

Flying can be compatible with neurodevelopmental conditions and some neurodiverse characteristics may even be advantageous in the role as cabin crew. It is important that the sector adopts appropriate practices regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion to encourage others to pursue careers as cabin crew.

A cabin crew initial medical is an in person physical assessment by a aeromedical examiner or occupational physician approved by the CAA. This usually commences with a questionnaire and declaration and then the physical assessment. When completing the medical questionnaire and declaration, it is essential to be truthful and obtain the available support if it is required. Medical requirements for cabin crew – information for airline operators | Civil Aviation Authority (caa.co.uk)

If a crew member has declared their neurodevelopmental condition and passed their fitness assessment, completed their training to the satisfaction of the operator and performs appropriately when flying then as with any condition this is acceptable. However, should any condition prevent a crew member from performing their day-to-day role appropriately, especially any safety-related duties, then this would have to be managed accordingly via the SCCM/operator.

-

CC6397

–

Strong smell of fuel in the cabinStrong smell of fuel in the cabinInitial Report

On taxi out there was a strong smell of fuel in the cabin, I rang my crew at the rear to ask them and they said it was very strong. I rang the Captain and asked are we behind another aircraft and drawing in their fumes to the cabin? He said he wanted to investigate. I asked him if he would make a PA, he said not right now? The smell was very strong, I had positioning crew in the cabin and I could see the SCCM looking at me, waving her hand in front of her face indicating that there was a smell in the cabin. 10 mins went by with no communication from the flight crew to our customers and they could hear the interphone call bell going off in the cabin by myself calling my crew at the rear and the flight crew calling them too. I was very frustrated that the flight crew left it for such a long time to communicate with our customers.

In the end, I asked one of my crew to walk through the cabin to show crew visibility and I walked from the front of the cabin to meet her. I verbally spoke to the forward passengers explaining to them that the flight crew are working through some checks and that we were aware of the smell in the cabin. Shortly after the captain made a PA, explaining what they were doing. We eventually returned to stand escorted by the fire services to a remote stand. The captain came out to talk to us after customers had disembarked to complete a report asking how strong the smell was, very strong. I did say to him in front of the crew that passengers had commented that the communication took a long time, he replied our checks and investigation of the smell takes priority over communicating.

Company CommentCabin crew receive annual training where some sessions are joint with flight crew. The aim of these sessions is to understand the workload associated in the flight deck when responding to an incident. Cabin crew are trained to recognise the flight crews’ order of priority: Aviate, Navigate, Communicate.

In this scenario, we know that as each minute goes by, in the cabin that could feel like it is taking far longer than it should. This is also discussed in various training courses and the perception of time when under duress. A duration of 5 to 10 minutes might not seem like a long time when we routinely talk about it, however in a pressurised situation it will feel much longer. During that time, if the conditions of the cabin change significantly the cabin crew (using the chain of command) should contact the flight crew using the emergency interphone call. We support the actions of the flight crew to focus on aviate and navigate whilst problem solving the reported incident which is likely to have increased their workload at that time e.g. communicating with the ground, using checklists etc.

Reporting (using our internal safety reporting method) is important for continuous learning and leads to reviews of procedures by the relevant teams e.g. flight operations, cabin safety and training. Real events feed into training and carve the way for us as an operator to understand a bit more about the incident and implement learnings or change, if that was recommended.

The reporter spoke to the customers, which we fully support. Providing information known at the time, and regularly helps the customers and crew know that something is going on and that the flight and/or cabin crew are responding to it. This is likely to be led by the SCCM.

CAA CommentCRM training places emphasis on the effective use of all available information to support decision making. In such a scenario as that described, flight crew will assess reports from the cabin crew, data from engine instruments, outside environmental conditions and possibly other sources such as ATC to ensure any actions are based on a sound decision. Where an aircraft is on the ground and there is no immediate threat to safety, there is more opportunity to diagnose and review before committing to action.

CHIRP Comment

The cabin crew are the flight crew’s eyes, ears, and nose in the cabin, and cabin crew must report anything unusual to the flight crew as quickly as possible and safe to do so, whether it be a smell or anything visual such as smoke, or a medical incident.

We know from training that the busiest times for flight crews differ from those of cabin crews, 10 minutes can feel like it goes very quickly (final landing checks come to mind), or it can pass very slowly such as when waiting for a gate on the last sector home.

On this occasion the SCCM consulted the cabin crew at the back of the aircraft to gather more information before sharing their concerns with the flight crew, just as the flight crew would need to consult their instruments, each other, cabin crew in the relevant area, and possibly third parties (ATC, engineering, etc.) to gather more information before making a PA to the passengers. The flight crew will be attempting to diagnose the situation and advise the passengers when they have sufficient information.

The SCCM was proactive by having crew walk through the cabin and communicating with the forward passengers. This could also have been backed up with a PA from the cabin crew to advise passengers that the crew were aware of the smell and more information would be available when possible.

-

CC6426

–

Crew Working Whilst SickCrew Working Whilst SickInitial Report

I recently flew with one cabin crew who spent the entire day coughing and was clearly sick. I commented at the end of the day to her that she did not sound well, which she acknowledged and agreed she was sick with a blocked nose and ears. I told her she should call sick and that she might pass her sickness on to other crew members and passengers, to which she responded that calling in sick would cause her problems with the company and that it is better to work sick. I have experienced this many times with flight crew, but especially cabin crew. The sick crew member is aware that they are sick, but is afraid of the repercussions of calling in sick from the company. There seems to be a culture of fear about going sick which is dangerous for the crew member who is sick, as well as crew and passengers they are responsible for.

Company CommentIt is each crew members responsibility to ensure they are fit to operate a duty. There is an established sickness process in place that crew are required to follow if they are sick. As with all companies, there is an internal process for following up with crew who call sick including checking their welfare. We have a number of crew who follow this procedure successfully. There are no repercussions should crew follow the correct process. We have a robust reporting culture that allows crew to report not only occurrences but safety hazards they see on the line. Crew can report internally using the safety reporting system or through the confidential reporting system.

CAA CommentIt is a requirement that a crew member does not report for duty when unfit to do so. It is recognised that companies may have sickness management policies intended to identify recurring sickness for welfare purposes, however, such policies should not encourage cabin crew to operate when unfit.

CHIRP Comment

Other than causing further illness and possibly injury, safety may be being compromised by crews feeling pressured to operate when they are unfit to do so, whether perceived pressure from your operator or personal pressures. We understand that pressures are not just financial but may be related to sickness polices, temporary contracts etc, but the safety implications of operating as crew when unfit to do so are clear. As a crew member you must ensure that you only report for duty when fit to do so.

MED.A.020 Decrease in medical fitness

- Cabin crew members shall not perform duties on an aircraft and, where applicable, shall not exercise the privileges of their cabin crew attestation when they are aware of any decrease in their medical fitness, to the extent that this condition might render them unable to discharge their safety duties and responsibilities.

UK operators like most companies are required to have processes in place to support employees whilst they are unwell. The CAA Flight Operations Group are doing some wider work with the industry on absence management which we will hopefully be able to update on later in the year.

-

CC6345

–

Reduced Safety EquipmentReduced Safety EquipmentInitial Report

During our preflight safety checks we became aware that there were 2 BCF extinguishers missing from doors 2 and doors 3, and 1 from the flight crew rest area. This meant that there were only 2 BCF in the cabin and 1 in the flight deck. On checking the tech log it revealed that the 3 BCFs had actually been removed at AAA.

I brought this to the attention of the flight crew who were adamant that we could go as long as we had 2 BCFS and 2 water extinguishers in the cabin. Apparently this was on the MEL but as cabin crew we don’t have access to that and flight crew did not actually show me. The BCF and water were all at doors 1 and 4 with nothing in between so, we repositioned them so we had 1 at doors 1 and 1at doors 3.

Only having 2 BCFs is less than half of our normal equipment, I find it totally unacceptable. A night flight with tired crew and I am having to try and remind them at every opportunity where the operational BCF are in case of an emergency and we spend most of the flight time over the Atlantic.

Company CommentThere are two responses to this answer. The first will is the regulatory explanation and the second addresses how this might feel on the day.

For the {aircraft type}…

- A minimum of 4 serviceable extinguishers are available in the cabin of which 2 must be BCF and one must be water; 1 serviceable BCF extinguisher is available on the flight deck.

- The regulation we refer to UK REG (EU) 965/2012 (Air Ops), contains a hand fire extinguisher section (CAT.IDE.250) and states various requirements including number installed. The minimum number of hand extinguishers with the maximum passenger seating operation on the {aircraft type} is 4. To meet this requirement, refer to point 1 above.

On this occasion, the flight crew’s assessment is correct and meets the regulatory requirements. Cabin crew do not have access to the MEL as it is a flight crew function. The role of the SCCM is to collect the equipment checks from the cabin crew and report their findings to the flight crew, which includes any anomalies. The Commander is responsible for ensuring the flight is operated compliantly, hence the flight crew consult the MEL as and when required.

We understand how the reporter felt when they were presented with 2 fire extinguishers in the cabin, when there is usually 4. They correctly repositioned the 2 they had throughout the cabin. The third being the water extinguisher and the fourth in the flight deck. If the reporter has completed a safety report, we would be able to share this feedback with the engineering team to ensure if equipment is missing it is repositioned. When we have debriefed previous incidents where a fire extinguisher was used, the crew reported that they used a few squirts to contain the fire. For most incidents, they did not use it apart from standing by with it. The main control is to break the components of the fire triangle where all three elements (fuel, heat and oxygen) are required to start a fire. Cabin crew are annually trained, and rehearse through practical means isolating electric’s which could prohibit ‘heat’. Examples are isolating the power by switching the oven off and pulling the circuit breakers, or switching the IFE off, or submerging a PED in water etc. Informing the flight crew immediately, will help as they will consult their checklists. They may further isolate power to various parts of the cabin too. Successfully completing this action will likely put or reduce the fire without use of the BCF, although crew will be standing by with a fire extinguisher just in case as part of the fire drill. The fire extinguisher lasts for about 15 seconds. This does not sound long when verbalised, but, using it, together with the volume of the extinguishant, means fully using a bottle is unlikely provided isolation measures, if applicable to the incident are followed. This response is based on the fires commonly reported in industry and experienced within our operation.

CAA CommentFlights are required to be operated in accordance with the Minimum Equipment List (MEL), which states the minimum permitted quantity of serviceable equipment required to dispatch a flight. Whilst cabin crew generally do not use the MEL it should be accessible for reference. Safety equipment should not be repositioned by cabin crew unless it can be correctly stowed in a location marked for its stowage, and only with the authority of the captain and ideally performed by an engineer.

CHIRP Comment

The Master Minimum Equipment List (MMEL) is a document, developed by the manufacturer and approved by the State of Design, that lists the equipment which may be inoperative at the commencement of flight without affecting safe operation of the aircraft.

Operators then produce their own Minimum Equipment List (MEL) which is approved by the Regulator but, if this differs from the MMEL, it may only be via the inclusion of more restrictive limitations. In the event of any defects being notified or arising before take-off, the Commander must review them against the MEL to ensure the aircraft can still be safely dispatched. The continued operation of an aircraft with permitted defects should always be minimised, though mitigations or alternative measures may be put in place until maintenance action can clear the problem.

The crew onboard should be working as a team, and if the SCCM is unsure of the content of the MEL then they should feel that they can clarify their concerns with the flight crew. The MEL is supposed to not only detail the allowable deficiencies but also how to comply with them, so the decision about how best to distribute the remaining extinguishers should be easily identified. The MEL should say exactly what is required and where it should be.

-

CC6453

–

Fatigue induced sleep whilst manning doorFatigue induced sleep whilst manning doorInitial Report

I operated two busy and long sectors. On outbound flight; arrived for duty 2 hours before report time. Commute to work was by car, taking approx. 1hr 30mins. After our flight briefing, we made our way to the gate but were informed aircraft was still disembarking pax and our crew boarding would be delayed by 1hr due to the late arrival of the aircraft. Arrived on time and got to the hotel at around 5pm local. Slept down route between 9pm and 1am local and could not gain more sleep despite efforts. I remained in my hotel room down route due to tiredness and the need to be rested and fit for duty on the return flight. However, on wake-up call, I felt like I had brain fog due to fatigue from poor sleep gained. I also felt anxiety at having to perform crew duty on another busy long sector flight, I did not feel adequately rested.

We left the hotel the next day at 3pm local. My position involved being responsible for a door on both sectors, we operated with one crew member less than the full-service complement. Both sectors were passenger flights with 80-95% pax load. On both sectors I had over 2 hours inflight rest taken in a bunk, both flights turbulent and no sleep gained. No other break periods taken due to busy pax services and demands.

On arrival back to UK airspace we were in a hold approach and I was sat on my jump seat for an extended period. I found myself fighting to not fall asleep. After landing we were stuck on the tarmac for 30 minutes due to a plane blocking our entry to the gate. During this wait I fell asleep on my jump seat, I estimate this was for a few minutes. My fellow crew members noticed and woke me up. This is the first time I have fallen asleep whilst manning a door in my 15+yrs career. It has shocked and concerned me in relation to failing in my duties around safety and security.

I believe and express in these reports that now pax numbers have increased since the pandemic, the airline is failing in a duty of care to ensure I am able to adequately rest and sleep. I do not feel the time given down route is sufficient. I report this every time. I have also included my anxiety around this and the increased demands this is having on my mental and physical health over time. I have previously stood myself down (once) siting cumulative fatigue after flights of this nature. On my return to duty the airline, whilst having to be supportive and non-punitive, have openly questioned me on my knowledge around my understanding of tiredness compared to fatigue. This induced a fear factor in myself making me less likely to call in unfit for duty due to fatigue on future flights. On reflection, I did not feel fit for duty on this return sector but feared standing myself down and impacting on the operation of the flight leaving them short of crew. I had a fear of reprisals from the company from this.

Company CommentWe are aware some crew find west coast trips challenging. We do however also receive positive feedback on these trips now as crew members are learning to manage their sleep effectively and appreciate the benefits of less acclimatisation when they return to base as their days off are less affected by recovery.

We continue to monitor the west coasts and for the W23 season there will be only 1 of these trips per day, which will lessen overall exposure to them. We are also looking at the possibility of limiting them to 1 per month from S24, but this has yet to be agreed and will depend on the feedback we receive over the winter whilst they are limited purely by frequency.

Reporting fatigued for duty is essential if a crew member does not feel fit to operate, and it is encouraged for the safety of our operation. Whether that is due to tiredness or fatigue is a conversation that is necessary in order to better understand how to manage any re-occurrence. It is in no way intended to be accusatory, it is a necessary part of the fatigue process and understanding the difference between the two can be helpful to all involved. They are similar, and in some cases almost identical, but understanding the circumstances in each instance of fatigue is key to managing it, and that is critical in our business.

CHIRP Comment

CHIRP frequently receives reports regarding fatigue and we empathise with the crew as some duties can be very tiring. We are all unique and resting methods before a flight, down route and post flight will differ from crew member to crew member. It is the crew member’s responsibility to make best use of opportunities and facilities provided for rest, it is also their responsibility to plan and use rest periods properly to minimise fatigue. Cabin crew should not be operating when they are unfit to do so.

Despite a crew member reporting for duty well rested, this report discusses common scenarios in which a crew member may get tired/fatigued whilst on duty.

If you do find yourself feeling tired onboard, simple activities such as taking a walk through the cabin, having something to eat, or sparking up a conversation with a passenger or colleague may help. Some people believe that a strong coffee or sweet food/drink can assist.

There is no universal definition of tiredness/fatigue, and its experience and perception are subjective. Please remember to report any incidents of fatigue back to your company, a Just Culture should promote continuous learning, including lessons learnt from fatigue reporting and crew should not feel that they are unable to report fatigue or any other safety concerns internally. If crew don’t report their fatigue (or any other safety concerns) then the data won’t be there to highlight any concerns and provide the company with accurate information when reviewing rosters, routes and schedules.

-

CC6348

–

Pushing for an on-time departure, compromising safetyPushing for an on-time departure, compromising safetyInitial Report

A massive push for on time departure. Feel like there is a blame culture for why crew don’t start boarding on time, with it being recorded on our files when it is out of our control. The timings are in a perfect world of everything running smoothly, I feel as a SCCM I’m rushing my checks to hound other people for theirs to pass on to the ground staff who wants us (from the company) to board 10 mins early.

I find myself shadowing crew members, mainly new crew or new to type of their checks as I’ll know I’ll get an email asking why the cabin was released 2 minutes late. It’s not good CRM to be going to my crew asking if they need help with their checks- it’s confusing to know what had been checked etc, they are their checks and AORs for a reason. We have to count everything, that takes time and new are just that NEW, they still don’t have a rhythm or routine. I feel awful having to keep asking as they rightfully take their time doing their checks. We all get to the aircraft at different times so I have no idea what checks have been done and by who, it there seems to be little or no time to get this done. As a SCCM, the last month or so has been the most stressful I’ve ever experienced flying, when in reality cabin crew are rarely the reason for flights not getting away on time. I feel the company are prioritising seconds and minutes over their crew being able to do their checks thoroughly and properly.

Company CommentIt is a fine balance between running a safe, secure and punctual operation in aviation – however, safety and security must never be compromised. As the reporter refers to, sometimes there will be extenuating factors, out of the control of the crew that could impact punctuality. The organisation’s focus on punctuality is no different to other UK and worldwide operators. For reasons where crew feel pressurised to complete safety and security checks, a safety report should be completed documenting the occurrence if, for example there are pressures on the completion of safety and security checks with as much objective information as possible to help the safety and security teams understand the issue.

Communication is key between all crew and ground staff. Concerns about pressure to board should be reported to the Captain, especially if safety and security checks are being compromised.

When cabin crew related delay reports are received, the cabin crew management and operations team are keen to learn the events and reasons that led to the flight not meeting its target time. The cabin crew management and operations team were contacted and a copy of the email communication that is sent to crew was reviewed. It states:

- There is no obligation to reply on a day off.

- The communication is not positioned as a performance issue.

- The communication seeks to understand ‘what happened’ to allow a review of the process and prevent recurrence.

It also identifies if crew require support – there are no punitive actions associated with the follow up.

There are many factors that contribute to on-time performance, it’s important that as a team we continue to engage, learn and deliver improvement.

Action has already been implemented from the responses already received. The team have received many responses to date. So far, changes have been made to some report times for more challenging flights and at stations where there is a long transit time through the airport. These adjustments will help crew complete their pre-flight safety and security checks in the time provided.

CAA CommentPre-departure safety duties should never be deviated from in order to achieve on-time performance. If errors occur or omissions made owing to actual or perceived pressure, these should be reported to the company using the occurrence reporting scheme.

CHIRP Comment

Please do not allow yourself to be pressurised into not completing your safety checks properly. ‘Pressure’ is one of the most frequently reported key-issue safety concerns to CHIRP. Be it commercial pressure, time pressure and/or peer pressure whether the pressure is real or perceived, the results are frequently the same, in this reporters case it may have caused anxiety, a fear of something being missed and poor CRM. Passengers should not be boarding the aircraft until all the appropriate checks have been completed and the SCCM should have the confidence to say ‘no’ if the crew are not ready to board. The safety and security of the aircraft must come first.

If the passengers are late boarding the aircraft, or any other reason that may cause a delay (checks/baggage/PRM/catering etc) then it is important to document exactly why. Operators often need to contact crew for clarification on why a flight has been delayed and this is normally a standard communication that allows delays to be monitored and potentially improved by the management.

-

CC6461

–

Crew Using Personal Phone Devices at Critical Stages of FlightCrew Using Personal Phone Devices at Critical Stages of FlightInitial Report

I felt compelled to report to yourselves my observations of the growing trend of crew members distracted by the use of personal devices during critical phases of flight (taxi, take-off and landing). They have a complete lack of safety awareness. Whilst I am happy to challenge my colleagues around this behaviour, I have found I have been dismissed due same rank on board. I have also on occasions witnessed this behaviour from the most senior crew member which makes reporting all the more challenging. I have reported my concerns to the company in the past however, this continues. I often feel if an emergency were to occur unexpectedly, I would be the minority of crew ready to react. This is a commonly observed culture.

Company CommentThank you for submitting a report about crew using their personal devices during the critical stages of flight. The policy in the operating manual for device use states that for the majority of the crews’ duty, it can only be used for operational reasons. Credit to the reporter for challenging colleagues when they contravene this policy. All incidents of this nature need to be reported in a safety report. When they are triaged by safety, reports of this nature are brought to the attention of the cabin crew management team to contact the crew member to reinforce the policy. Safety reporting is crucial to allow us to build a picture of the trend and report to the various teams within the organisation.

CAA CommentReporting such incidents enables an operator to identify adverse trends and determine the root cause. Whilst appropriately addressing non-adherence to procedures with the individuals concerned may provide corrective action in those cases it is unlikely to provide a preventative measure that stops others from doing the same. Establishing the reason for an event is essential to enable the implementation of effective measures to prevent a wider re-occurrence.

CHIRP Comment

Using any sort of PEDs whilst engaged in other tasks can cause distraction. Taxi, take-off and landing are classed as critical phases of flight and cabin crew should not be using personal devices during this time. There can be all sorts of circumstances that make it difficult to wait and whilst it may be tempting check your socials or send a quick message during the critical phases of flight, cabin crew members must be focused on the tasks ahead and be ready to act should an emergency situation arise. If an operational task requires it, cabin crew can use an electronic device as per their company Operations Manual which will specify the situations when this is permissible.

The reporter raises an interesting and important point around the psychology and effectiveness of training. The operator changed its strategy several years ago after feedback showed cabin crew were nervous about the annual recurrent training event. Their entire focus was on passing the exams. The exams were old fashioned written papers which required the delegates to precisely answer the wording in the manuals. This led to a behaviour that instructors would deliver training focused on passing the exams and the delegates would just remember those bits. The wider purpose of the day was lost. Furthermore, the whole class was given the same or similar questions, which were then circulated.

We want to drive a joint pilot/cabin crew training day that allowed delegates to focus on developing their skills and learning from group facilitation. We want them to leave not just with a pass, but to take safety and CRM “to the aircraft”. The intent is to make the training day a professional-to-professional event, in style more like a conference or workshop than a school class. So, in conjunction with the authority, it was decided to publish the entire question bank to allow revision prior to the event. On the day, no one person receives the same exam. Each delegate is pushed a random selection electronically to their electronic device.

Cognitively, revising by self-testing is for most people more effective than simply reading a manual. Forcing the brain to retrieve information builds pathways to make subsequent retention easier. That is why Computer Based Training generally has questions at the end to test understanding and reinforce the learning.

Whilst there are differing opinions as to the efficacy, evidence appears to show that this approach has not unacceptably reduced knowledge, although the operator does accept the industry wide problem that generation Z does not like rote learning.

Let’s examine safety incidents for which crew error is the primary cause, for example, inadvertent slide deployment. Crew interviewed after these events can invariably recount the correct procedure and process – so applied knowledge is not the problem. Normally the problem is either inattention (rare), fatigue (sometimes), distraction (common) combined with another simultaneous task that should have been given a lower priority (very common).

If we look at safety incidents that are not crew errors (e.g. oven fires, disruptive passengers, medical emergencies, etc…), these are generally well handled using a mixture of knowledge, CRM and reference to the Cabin Crew Quick Reference material which is held on each crew members iPad. This leads us to conclude that our training events are effective and focussed correctly on competency rather than just raw knowledge. All the operator’s cabin safety instructors are also qualified CRM instructors.

The operator will continue to monitor the effectiveness of the training approach, but current evidence suggests that on balance this is the right strategy. Crew are also encouraged to report any concerns or hazards via our safety reporting system. Reports are treated confidentially but if they wish to protect their identity further they have the ability to submit anonymous reports.

Training is intended to provide a benefit to those attending that they can apply in the operational environment. In making this comment, the number of questions in the question bank is not known, however, it should be such that it would make it very difficult for trainees to effectively remember each question.