FEEDBACK

Flights Reach Record High

Safety/Service Balance Ever Important

According to IATA, traveller numbers in 2025 are expected to hit 5.2 billion worldwide, up 6.7% compared to 2024, exceeding the 5 billion mark for the first time, with the number of flights expected to reach 40 million. As the majority of CHIRP reports received in 2024 reveal the increasing pressures faced by crew members, whether it’s perceived pressure or actual pressure, the effect on the crew member can be the same. Passengers may not see these difficulties, but behind the friendly greetings and great service, many crew members are increasingly finding it difficult to strike a balance between safety and service.

As the aviation industry continues to expand, it is more important than ever to report your safety concerns internally. Analysing data from their own reports is the most effective method for an operator to spot any potential issues. CHIRP does not replace organisations’ Safety Management System (SMS) and, if they feel able, cabin crew should always consider using these first before coming to CHIRP because this may result in a faster and more integrated response from the organisation. We understand that raising safety concerns can sometimes feel challenging, so if you feel unable to report them internally, you can report your concerns to CHIRP. Your concerns will be handled confidentially, with no fear of repercussions or identification.

Stay safe,

Jennifer Curran

In 2024, CHIRP received 349 cabin crew safety-related reports vs 335 in 2023.

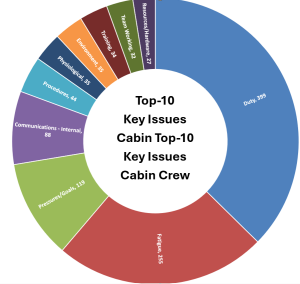

The top-5 key issues reported by cabin crew to CHIRP in 2024 were:

-

- Duty;

- Fatigue;

- Pressures/Goals;

- Internal Communications;

- Procedures

This shows a slight difference from 2023, with an increase in reports to CHIRP related to Pressures/Goals. This trend is evident in the reports featured in this edition. The top-5 key issues reported by cabin crew to CHIRP in 2023 were: Duty; Fatigue; Internal Communications; Pressures/Goals; and Resources/Hardware.

Each report submitted to CHIRP is coded and CHIRP use the ICAO Accident/Incident Data Reporting (ADREP) taxonomy, which is a set of definitions and descriptions used during the gathering and reporting of accident/incident data. It’s not unusual for a report to be allocated multiple ADREP codes, for example the ‘Duty’ taxonomy is split down into 7 sub-categories: Crewing; Discretion; Disruption; Length; Other; Rest; and Rosters/Rostering/Shift. A single report could be allocated multiple codes, such as Discretion; Length; Disruption; and Fatigue.

After 4.5 years as the CHIRP Director Aviation, Steve Forward is retiring. We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to Steve for his dedication, thoughtful leadership, and valuable contributions to improving aviation safety. We wish Steve a very happy and well-deserved retirement – thank you!

Nicky Smith joins CHIRP as the new CHIRP Director Aviation. Nicky’s aviation career started in 1986 on Cambridge University Air Squadron. She served in the RAF for 22 years in total, flying Jet Provost, Wessex, Bell 412 and Sea King, amongst others. With a move to Commercial Aviation in 2011, Nicky flew as an Air Ambulance pilot for 11 years in both East Anglia and Wiltshire. During this time, as the Safety Manager, she also established and ran an SMS for a small AOC, which is where she gained an increased interest in aviation safety. Over the last couple of years, she has found innovative ways to promote safety and Human Factors throughout the MOD’s Joint Aviation Command.

We’d also like to thank Kirsty Arnold who has stepped down as the CHIRP Cabin Crew Advisory Board Chair. As the original Cabin Crew Programme Manager in 1996, Kirsty has been a tremendous addition to CHIRP, and we are incredibly grateful for all that she has done for the organisation over the years.

For more information on the CHIRP team Meet our team – CHIRP and the CHIRP Advisory Boards please click on the relevant link Aviation Advisory Boards – CHIRP

Jennifer Curran

Cabin Crew Programme Manager

-

CC6722/FC5376(C)

–

Commercial PressureCommercial PressureInitial Report

CC6722 Commercial Pressure

We have an SOP whereby pax are released on first-wave flights automatically without crew consent. Years ago, our report time was -60 and in the countdown to departure, we were allocated 10 minutes to brief, 10 minutes to reach the aircraft and 10 minutes to do our pre-flight checks (PFC) and searches. There was then a push for briefing onboard rather than in the crew room, but the crew still left the crew room together as a team and therefore could chat on the way to start building up CRM. There was then a gradual shift to “report to aircraft”, meaning crew would arrive individually, and now ALL of our flights are report to aircraft, meaning we don’t meet each other until we are onboard or at the gate. Report time was -60, we were told to be onboard the aircraft by -45 at the latest and green light boarding (GLB) was moved to-30 rather than -25. We therefore had 5 minutes less, in practice, to do everything we previously had 20 minutes to achieve, and nothing substantial had changed in the briefing structure or our checks onboard. A thorough and compliant security search, along with PFCs on equipment takes just under 10 minutes, if not longer, depending on the experience of the crew (at our base, the biggest in the network, we have a lot of inexperienced cabin crew.) This therefore leaves 5 minutes for the combined briefing between flight crew and cabin crew. We also have to allow time for the HUMAN FACTOR in what we do – saying hello to each other, building rapport etc rather than just diving right into formalities. The company seemingly does not see things this way.

GLB in other bases is achievable given the infrastructure of the smaller airports. If at security at -60, in some bases the crew can be onboard by -55, allowing them 25 minutes before GLB. In our base, which is a huge airport, it sometimes takes 15 minutes (or longer) to clear security and walk to the gate. There is therefore even less time to brief and do our checks. As a trial for the summer, we were being asked to report at -75. I had thought, naively, that GLB time would either remain at -30 or at least be moved to -40, but it is in fact now -45. Meaning we are being asked to report earlier, but are being given no extra time to achieve everything we need to prepare the cabin for pax. When report time was -60 and GLB was -30, the target was often met through the goodwill of the crew reporting earlier than -60 (which is obviously not reflected in our Flight duty period). Now that report time is -75, GLB is consistently not being achieved, and the blame placed squarely at the feet of the cabin crew.

I strongly believe this is because the crew’s goodwill has run out and they are no longer prepared to report earlier in order to achieve the unachievable. In response, the company has sent a barrage of emails, which I would describe as textbook commercial pressure, some quite threatening in tone. Any SCCM who does not achieve GLB will have a meeting placed on their roster. The company says the meetings are non-punitive, but are they really? An incentive was started in which crew could win a prize if GLB was achieved. And most worryingly of all, we were told that cabin crew could choose their own working positions on arrival at the aircraft if the SCCM was not yet there, and start their checks. This contradicts our briefing procedure which states that positions should be “discussed based on crew preference”. If one cabin crew member arrives at -70, the next arrives at -65 and the last arrives at -60, that last cabin crew member gets no say in where they work, even though they are not late. This is grossly unfair. The company is incentivising crew to report early in order to get their choice of working position and also potentially cut corners/skip part of a briefing in order to a win a prize. This is all smoke and mirrors to distract from the fact that they are simply not giving us enough time. Instead of giving us more time, they send threatening emails and tempt us with winning prizes.

FC5376 Commercial pressure

Green light boarding is a term used within the company to start boarding at or before a certain time. It has had a lot of focus, and it seems the company believe delayed boarding is the root cause of delay. In order to achieve Green Light Boarding, it has for a while been linked to the cabin crew performance bonus. To start boarding, the cabin needs to be ready and more importantly safety and security checks needs to be completed. To put these procedures under time pressure is not good practice. Recently, boarding automatically start at a certain time. That means, unless the crew actively tells the ground staff to hold the boarding, passengers will start coming up the steps at a given time. This adds more pressure on the cabin crew. It is escalated further by management contacting cabin crew directly, when Green Line Boarding is not met. Sometimes before they have finished their duty. They are asked to explain why the target wasn’t met. When there is so much time pressure how is anyone meant to know why things are 2 or 5 minutes delayed. My experience lately is that some SCCMs are trying to cut corners in order to achieve the targets. We always have a briefing when the day starts. The whole crew gets a chance to greet each other, and discuss what is expected of the day. It builds the team, and is often a good chance to highlight any potential issues. On two occasions over the last weeks, SCCM have tried to skip the briefing with the entire crew. When I insist, they immediately mention concerns that we are meant to start boarding imminently. It is obvious to me the cabin crew are under pressure.

CHIRP Comment

Last year, nearly 60% of CHIRP reports, including those from flight crew such as FC5376, highlighted significant pressures within the system. These reports, along with the two examples above, reinforce the concern that crew members may feel compelled to take shortcuts in order to meet targets or deadlines. It is crucial that crew members resist the urge to compromise safety in order to meet operational targets.

All concerns, regardless of their size, should be reported to your operator. CHIRP recognises that reporting may sometimes feel unproductive, but it is essential that you continue to report, even if you don’t receive feedback. It is important to communicate to your operator if the current timings aren’t working or if adjustments are needed. Your feedback plays a vital role in highlighting the challenges so that improvements can be made.

-

CC6742

–

Further admin duties added prior to report timeFurther admin duties added prior to report timeInitial Report

My operator is conducting a trial where all allergen information must be downloaded by crew prior to our flights. This wouldn’t be an issue if we had nothing else to download/look up/log in etc and had a robust, flawless IT system. As a SCCM it takes me on average anything between 20-40 mins to download, log in, etc all docs and portals before each flight.

How much more work and how early must we actually get to work and to our report centre prior to our briefing time? Considering we already do a LOT of work prior to our FDP commencing and have to be there a long time prior, this is one step too far. I’m fed up with having to come to work early and spend so long doing work that’s unpaid and doesn’t count towards my duty when it is absolutely imperative this it is done before I fly.

If we don’t have allergen information my operator is putting the lives of customers and colleagues at risk due to potential severe allergic reaction, however it is well and truly impacting our rest prior to a duty. It may just seem like an extra 5-10 mins (our systems are quite shocking to log into) but adding that to everything else, it is just too much. We are already asked to do too much before our FDP actually starts. When is our rest time not our actual rest?

Company CommentAllergen information is currently available onboard in a paper format along with the onboard catering paperwork on each flight. There is usually a lot of information contained within the allergen lists as they pertain to all routes and all the different types of services we cater for. To help reduce the volume of information, the catering team were trialling a new proposal to communicate flight specific allergen information using an app. The trial lasted for 3 months on a small number of routes. For the trial routes only, paper copies were removed, and crew were instructed to access the allergen information via the app. The trial sought feedback from crew and was regularly reviewed by the project teams. The trial was communicated to crew formally using the operations manual as a temporary notice to alert all crew, and a reminder was included in the briefings for the trial flights only. When tested, the app opened normally using either Wi-Fi or mobile data. As all crew are supplied with a device, the accessibility to the app meant more than one could have access, instead of one paper copy currently loaded.

Whilst most of the feedback received was positive in terms of accessibility of information via the device, there were some other useful bits of feedback too. Following a review of the system and IT process, feedback from the trial the project team acknowledged that the app is not a suitable platform for this information. There was an increase in multi-factor authentication triggers, and this had been identified as a significant risk to crew being able to access allergen information.

A decision was made to migrate the allergen information from the app to DocuNet i.e. accessible to all crew in the same location that our operations manuals are located. Once fully implemented, we will communicate to all crew and update the procedure in the operations manual. There will be no further tasks to complete to what the crew have always done before i.e. ensure that DocuNet is updated prior to when the crew board the aircraft. It means that allergen information is available to all crew from their company issued device like the operations manuals, passenger lists and other operational information.

CAA CommentA flying duty period (FDP) starts at the time of report and this should include sufficient time for the completion of pre-flight activities without crew members feeling the need to report earlier in order to achieve these duties when this additional FDP is not recorded.

Time taken to perform duties at the behest of the operator are required to be appropriately recorded for the purpose of compliance with the approved flight time limitations (FTL) scheme and monitoring cumulative duty hours.

CHIRP Comment

As aviation professionals, cabin crew are expected to stay up to date with essential preparations before reporting for duty, such as reviewing safety notices and other relevant information. However, there is a limit to how much can reasonably be expected of employees outside working hours. The small additional tasks and time spent – five minutes here and there – can accumulate into a significant amount of extra time that isn’t accounted for in your FDP and FTLs. Equally, crew should always be mindful of their FTL and avoid arriving too early for report; even a quick there and back can turn into a lengthy duty.

Of course, operators are continuously seeking ways to improve efficiency. As noted in the company comment, the trial was deemed unsuitable based on feedback from crew members. This is another reminder of why it is crucial to report any safety concerns to your operator. Without input from crew members, as if no feedback was received to suggest otherwise, trials may be implemented without full awareness of potential issues. Your feedback is essential in ensuring that changes are beneficial and practical.

-

CC6807

–

Unable to secure cabin properly. Loads too high and too much pressure on crewUnable to secure cabin properly. Loads too high and too much pressure on crewInitial Report

We have recently been finding ever increasing loads. As crew we are put under serious pressure to prioritise and give full service. Again today this led to ten minutes to landing and a cabin full of trays and glasses. Crew risked injury trying to get cabin secured for landing with little and not enough time. We ended up landing with items in the toilets that should have been away and the PED (portable electronic device) power still on, posing a fire risk. As the SCCM onboard I have yet again been put in the position that the company are prioritising profit and service over safety.

Company CommentThe Senior Cabin Crew Member (SCCM) is responsible for ensuring that cabin service is delivered safely on behalf of the captain. During the briefing, there is an opportunity for both flight and cabin crew to discuss key factors impacting the flight, such as load, service requirements, and weather conditions. Given that this information is available at report, it should be reviewed and a plan established. For instance, the team might agree to begin pre-landing preparations 15 or even 20 minutes before landing, instead of the standard 10 minutes.

SCCMs are encouraged to use available information to plan and prioritise effectively, ensuring safety remains the top priority. If the service timeline begins to interfere with pre-landing preparations, maintain communication with the flight crew and consider ending the service early if needed. In such cases, document the decision and its rationale in a cabin safety report.

CAA CommentWhere the passenger cabin cannot be secured for landing it is essential that this is communicated to the flight crew; confirmation of “cabin secure” is required as part of pre-landing standard operating procedures (SOPs). It is not acceptable to place cabin service items in lavatory compartments as these are not designed as stowage’s.

Communication between the cabin crew and flight crew is paramount to establish flight duration, time of start of descent, time of cabin secure and any changes to these times to enable the SCCM to plan and monitor cabin service activities such that they can be completed prior to the time the cabin is required to be secured for landing.

CHIRP Comment

The primary reason cabin crew members are on board is to ensure the safety and well-being of the passengers, and a crew members’ top priority must always be safety.

If a full service cannot be completed, adjustments should be made accordingly and these changes documented for the operator to review.

-

CC6813

–

23.5 hour long duty from standby call out23.5 hour long duty from standby call outInitial Report

I had a 0700-1300 standby block, 5 days in total, and was called on day 1 for a flight that didn’t report until 15:20. It then had a delay to report at 16:20. I raised this with the crewing team on the initial call and said that I started my standby at 7am and that this would be out of my block. They advised that I would have a 2 hour 35 min break, which increased to 3 hours after I raised that we had an hour delay so this should be accounted for. I was called out with another crew member on the same standby block and we both pushed back to the company that this wasn’t an acceptable time given the length of duty, but was told we must complete the duty.

The flight was 10 hour 25 mins and we arrived at the destination at 21:18 local (05:18 UK time). After disembarking and travelling to the hotel, we didn’t arrive at the hotel until 22:35 local (06:35 UK) meaning my duty was 23 hours 35 minutes long. Both myself and the other standby crew member felt exhausted by this point. Given the -8 hour time difference in the west coast destination, it’s hard to maintain a good sleep pattern regardless of the length of duty.

We were told that the standby block times aren’t relevant to the call out time, and that they don’t count towards duty hours. We were also told the 18 hour awake rule didn’t apply as we had a 3 hour break, but given the duty we were awake for over 19 hours including the 3 hour break (7am to 5am = 22 hours, – 3 hours break). The company should have either pre allocated the duty the night before, as they were doing with other crew on the same standby, or allocated it to crew in a later standby block. They should consider following standby block times more rigorously to minimise fatigue. Standby rules should be written clearer too, as each person we spoke to gave us different information.

Company CommentHome standby duty for cabin crew is 6 hours (reduced from 8 hours as part of a scheduling agreement), although FTL regulations allow for 12-hour home standbys. There is no rule mandating the report time of the duty assigned must start within the duration of the standby, although the crew member must be notified during the standby period.

The start time of an FDP where inflight rest is taken cannot be more than 8 hours after the beginning of the standby, therefore in this situation, the FDP would begin at 1500z, not the scheduled 1520z. With a 1500z report time and 3 hours inflight rest, this takes the total allowable FDP to 17 hours, so the crew member was well within the limit.

As per OMA, ‘A crewmember should only be called out from standby to operate a flying duty that will result in an “awake” time of over 18 hours if the minimum in-flight rest is available’. As inflight rest was required, the awake time rule does not apply.

An appropriate fatigue mitigation is the allocation of inflight rest, which is supported by OMA.

I’m unsure what the time crew member was called out, however as they are not required to be on duty at the start time of their standby and resting at their place of residence. While the standby is considered a ‘duty’, only 20 minutes in this situation count towards the duty period on the day, which was the difference in report time and 8 hours after the start time of the standby.

The point about the duty should have been pre-allocated is not valid; the purpose of standby is to cover flights at short notice. If flights are sometimes allocated early, but it’s not always possible due to absence on the day and to maintain some flexibility in the operation.

Without listening to the call between the crew member and Crewing around the words used in relation to they ‘must complete the duty’, I can’t comment on whether the conversation was appropriate or not, however the allocation of the flight was compliant as described above. If the crew member felt they were too tired to safely operate, they have a responsibility as per OMA section 7.

OMA Crewmember Responsibilities

Crewmembers shall:

(1) Comply with all flight and duty time limitations (FTL) and rest requirements applicable to their activities.

(2) When undertaking duties for more than one operator;

- a) Maintain his/her individual records regarding flight and duty times and rest periods as referred to in applicable FTL requirements; and

- b) Provide each operator with the date, start time, end time, duty time and flight time to ensure such activities are planned in accordance with the applicable FTL requirements.

(3) The crewmember shall not perform duties on an aircraft if they know or suspect that they are suffering from fatigue or feel otherwise unfit to the extent that the flight may be endangered.

(4) Make optimum use of the opportunities and facilities for rest provided and plan and use their rest properly.

(SEP Manual) OMB Cabin Crew Fitness to fly

Each crewmember is responsible for ensuring that they do not perform duties on an aircraft or whilst attending training:

(1) When under the influence of psychoactive substances or alcohol; or when unfit due to injury, fatigue, medication, sickness or other similar causes.

(2) Until a reasonable time period has elapsed after deep water diving, or following blood donation. (See below).

(3) If applicable medical requirements are not fulfilled.

(4) If they are in any doubt of being able to accomplish their assigned duties.

(5) If they know or suspect that they are suffering from fatigue or feel otherwise unfit, to the extent that the flight could be endangered.

CAA CommentIt is possible during a standby period to assign a duty that will start after the rostered end of the standby period. Duties assigned during a standby period should in principle start within the operator’s defined response time from the call.

The response time between the call and reporting is considered a continuation of the standby, notwithstanding the rostered end of the standby; this time also includes travelling to the reporting point. As per CS .FTL.1 225 (b) (5) standby ceases when the crew member reports at the designated reporting point.

Operators should describe within their procedures and practices regarding standby, including reporting after the rostered standby period ends. In doing so, they take into account that the Regulation provides a number of cumulative protections to crew members from excessive periods of combined standby and duty such as :

- Operators shall only use the rostered standby availability period to place their call for duty. ORO.FTL.105 (25) defines standby as the period of time during which a crew member is required by the operator to be available to receive an assignment for a flight.

- The regulations state the maximum duration of standby other than airport standby is 16 hours, however an operator can state in their OM-A a shorter period considering its type of operation and the impact of the time spent on standby on the duty that may be assigned.

- Under the obligations of ORO.FTL.110 (b & e), operators must carefully evaluate what duration of standby is safely allowable within their particular operation.

- The combination of standby and FDP does not lead to more than 18 hours awake time .

- The maximum FDP is reduced, if the standby period ceases after the first 6 hours (or 8 hours in case of extended FDP);

- A crew member is always able to consider whether his/her duties on board an aircraft will be performed with the necessary level of alertness [CAT.GEN.MPA.100(c)].

Operators also have to demonstrate understanding of how fatigue could affect a crew member’s alertness and performance, how fatigue does or could occur within the working environment and the need to manage it effectively for continued safe operation.

It is also important that flight and cabin crew are actively encouraged to report fatigue related occurrences and issues relating to current and ongoing changes to the operation and operational environment. All crew members must be able to self-declare that they are fatigued and potentially unfit to fly within an open reporting and just culture principles as defined in EU 376/2014 without fear of punitive action.

CHIRP Comment

While it is clear that the time spent on standby does not always count towards the duty period, it’s important that both crew and management work together to ensure that these extended duties do not result in fatigue. In this case, the duty spanned nearly 24 hours, which is beyond what could be considered sustainable.

It is important to remember that if after a rest period and before reporting for a subsequent flight duty period, you have either not been able to achieve sufficient rest or think you could be suffering from the effects of fatigue, that you assess whether you are fit to operate the planned duty period and report as such to the company. There is a responsibility on each cabin crew member to ensure that should they not be able to perform the duties expected of them, they report this to their operator.

CHIRP have reported previously that the UK CAA have commenced a post-BREXIT review of the assumptions within the whole UK rostering and flight time imitations/ flight duty period (FTL/FDP) regulatory set so that they can determine whether there are any areas that could be better defined, harmonised or re-evaluated now that we are no longer part of the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) regulatory regime. We look forward to the outcome of this review for clarification of many parts of the FTL Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance Material (GM).

Once the stakeholder questionnaire responses have been collated, digested and recommendations have been formulated, the next step will be to consult with the wider aviation community to ensure that the views of those engaged in commercial aviation activities are taken into account.

-

CC6793

–

Fatigue reporting and processFatigue reporting and processInitial Report

I came back from long haul flight on Thursday morning having had no sleep for the night before. I was exhausted and later in the day put in a fatigue report. I have noticed over the last few months I was beginning to show signs of fatigue and tried mitigating these with rest. However I was run down and constantly exhausted. During my last few blocks of leave I have been unwell with colds/ coughs and general illnesses we pick up when run down.

When I called my operator yesterday morning I was absolutely shattered even after the two days’ rest. I had to argue with the person who answered the phone that I was fatigued and not unrested, which she kept telling me I was because I’d said I’d been awake for a period before my alarm.

Today I had a call from the safety department. I was told fatigue “isn’t” accumulative and that my operator only looks a few weeks back on the roster, and that as I’d put in my safety report for the actual fatigue incident yesterday together with that I had been ill on my leave a few weeks ago they were going to mark me as unrested. The safety colleague said nothing on my roster supported my claim to be fatigued as it was all legal.

I told them I was quite familiar with the CAAs provisions on the subject and that fatigue indeed is accumulative. Having noted in my report that in the last two months I’ve lost 8 nights of sleep, I am exhausted and I reported fatigued, because I am fatigued and that’s my right to do so. To which they tried to argue the case of my health being the factor for my tiredness, to which I explained my health goes in hand in hand with the amount of sleep I have lost, which is noted on the CAA’s website regarding fatigue.

I was adamant that they log it as fatigued and not unrested and reminded them this was my right to do and I shouldn’t be questioned over it.

I believe my airline uses different roster codes so they don’t show as a concern with multiple reports of fatigue.

Company CommentCrew members are personally responsible for ensuring they are fully fit, well-rested, and ready to perform all required duties when reporting for duty. If a crew member feels unfit to fly, they should follow the local policy in Operations Manual Part A (OMA), which outlines the fatigue management process for cabin crew. Reporting for duty indicates that crew members are prepared to safely operate for the maximum flight duty period. If any change in alertness occurs during duty, they must inform both the Commander and the SCCM. Crew members should not perform duties if experiencing fatigue or feeling unfit in a way that could impact flight safety.

After completing a duty or series of duties, it’s natural for crew members to feel tired; designated rest days are provided specifically for recovery, free from work obligations. However, if a crew member still feels fatigued and is unable to rest adequately before their next duty, whether the night before or on the day of reporting, they should follow the fatigue management process outlined in the OMA.

The safety team investigates fatigue cases using details from the safety report and discussions with the crew member, which then guide any necessary follow-up actions. Based on the findings, the crew member’s status will generally be categorised as either Fatigued, Unfit, or Unrested. These categories fall within the fatigue management process rather than the sickness policy and are identified specifically on the roster as fatigue classifications: fatigue-unrested, fatigue-fatigued, or fatigue-unfit.

CAA CommentOperators are required to comply with their Flight Time Limitations Scheme OMA Section 7 to ensure that crew members are adequately rested at the beginning of each flying duty period, and whilst flying be sufficiently free from fatigue so that they can operate to a satisfactory level of efficiency and safety in all normal and abnormal situations.

Crew feedback and non-punitive reporting are essential elements of an operators fatigue risk management. Furthermore, reporting processes should enable operational personnel to raise legitimate concerns regarding fatigue without fear of retribution or punishment from both within and outside the organisation. The Air Operations Regulation 965/2012 provides details on the shared responsibility obligations of both operators and crew members regarding fatigue, namely:

- ORO.FTL.110 Operator Responsibilities

- ORO.FTL.115 Crew Member Responsibilities, and

- CAT.GEN.MPA.100 Crew Member Responsibilities.

In essence, these requirements can be summarised as follows:

- The operator is responsible for creating rosters that enable crew members to perform their duties safely, and implementing processes for monitoring and managing fatigue hazards.

- Crew members are responsible for reporting fit for duty, including making appropriate use of rest breaks to obtain sleep, and for reporting fatigue hazards.

A roster may be compliant with prescriptive limits or industrial arrangements, but the operator is responsible to ‘ensure that flight duty periods are planned in a way that enables crew members to remain sufficiently free from fatigue so that they can operate to a satisfactory level of safety under all circumstances’ – under ORO.FTL.110(b).

CHIRP Comment

This report highlights some challenges that cabin crew can face when it comes to managing and reporting fatigue. As the effects of fatigue and an individual’s susceptibility to it are not an exact science, it is up to the crew member to decide if they are fatigued or not. Until an agreement is reached to the contrary, if a crew member feels fatigued, fatigued is what should be recorded. It takes courage to defend yourself if you feel under pressure, but this is the right thing to do and ensures that fatigue and roster issues are captured accurately. CHIRP understand that there is work going on in the UK CAA Flight Operations Liaison Group to review fatigue reporting best practices.

The reporter describes being “run down” and struggling with fatigue over an extended period, which included multiple bouts of illness. This indicates that fatigue was not a one-off incident but a cumulative issue. Losing sleep over time adds up, fatigue can be accumulative, their feeling of exhaustion may have been directly related to that sleep debt. A sleep debt, is the gap between the sleep your body needs and the sleep you actually get. For example, if you need eight hours of sleep a night but only manage to get six, you’ve accumulated two hours of sleep debt.

There is a responsibility on every crew member to ‘make optimum use of the opportunities and facilities for rest provided and use rest periods properly’ as stated in UK Regulations ORO.FTL.115 Crew member Responsibilities. Both at home and down-route, this can be difficult. How to mitigate the potential effects from a sleep debt is down to the individual, some crew sleep for a few hours after earlies or a night flight, whereas some crew power on until the early evening. NASA have found that short power naps can increase performance, vitality, and productivity, so maybe a nap is the answer. It’s also important to recognise that what may have suited an individual a few years ago, may not still be the case. For information and advice on sleep please click on this link How to fall asleep faster and sleep better – Every Mind Matters – NHS (www.nhs.uk)

Thank you for sharing your concerns regarding the recent changes to report and green light boarding (GLB) times. We want to assure you that safety remains at the forefront of everything we do. None of our operational decisions compromise safety, and we are committed to maintaining the highest standards. At the same time, we recognize the importance of balancing safety with our customers’ expectations of on-time performance, which is central to the {operator} experience.

The adjustments to GLB and report times at {airport}, particularly the introduction of the -75 report time, aim to streamline operations and ensure timely departures. We understand that larger bases like {airport} present unique challenges, which is why we launched the -75 report, allowing more time to navigate these complexities. The trial has been positively received overall, leading to improved roster stability and enhanced on-time performance, benefiting both crew and passengers.

Based on extensive trials, we know that GLB milestones can be met without compromising SOPs. The SCCM plays a crucial role in ensuring all pre-flight safety requirements are completed and has the authority to communicate with ground crew if additional time is needed before accepting passengers. This ensures that safety protocols are fully adhered to and that no corners are cut.

We also recognize the importance of teamwork and rapport among crew members. While individual arrivals at the aircraft are designed to streamline operations, we value the crew collaboration and communication that occurs onboard. We encourage the proactive use of time on board to foster team spirit, and the SCCM is empowered to reassign working positions during the briefing to support crew preferences and operations.

Feedback from our crew is critical in refining these processes. We operate in a Just Culture, meaning that issues related to GLB or timing are not about blame but about learning and improving together. Meetings with Base Management are intended to gather insights and address challenges constructively, not punitively. Initially, meetings were assigned to gather feedback quickly due to our decentralized debrief process. However, we’ve listened to crew feedback, and the {airport} base team now offers the flexibility to debrief via email, providing a preferred and more flexible communication channel.

We also recognize the concern around incentives. This was designed to acknowledge crew efforts but has since been removed to ensure the focus remains on achieving operational goals for our customers, without any perception of incentivizing fundamental responsibilities.

The GLB process was thoroughly trialled and reviewed by working groups before its implementation, with safety being the primary focus. On-time performance is achieved through teamwork, and while the automatic release of passengers ensures smoother customer experiences, we acknowledge the specific challenges at larger bases like {airport}. The -75 trial was designed to improve stability and enhance performance across the day, and we will continue to listen to and analyse crew feedback to ensure this process aligns with operational needs and crew well-being.

We have continually invested in upskilling our SCCM community to ensure they feel empowered in their leadership role, to ensure all safety checks are fully completed and encourage proactive communication as part of a cohesive team effort between flight crew, cabin crew, and ground staff.

Your feedback, particularly regarding the pressures felt at larger airports and the current infrastructure, is incredibly valuable. It helps us continuously review and adapt our processes, ensuring we meet commercial objectives while prioritising the safety and well-being of our crew. We are always open to further discussions to ensure that our operations continue to reflect both the needs of our teams and our commitment to delivering safe, efficient, and on-time performance.

A flying duty period (FDP) starts at the time of report and this should include sufficient time for the completion of pre-flight safety responsibilities without crew members feeling the need to report earlier in order to achieve these duties when this additional FDP is not recorded.

Incentivising on time performance carries the potential for crew members to prioritise this at the expense of completing operational duties to the required standard and may create a perception of pressure. Pre-flight safety duties are required to be completed in accordance with the Operations Manual and deviation for the achievement of on time performance is not acceptable.