FEEDBACK

Making change happen

CHIRP provides a vital safety net when normal channels don’t deliver the results

As I write this editorial we’re approaching halfway through the year so I thought it would be useful to give an idea of the main themes reported to CHIRP in these first 6 months. The chart shows the associated top-10 Key Issues reported to us across the Air Transport sector and, for those who are interested in the breakdown of each Key Issue, the sundial chart at the end of this editorial shows the principle sub-issues for each (the Key Issues are in the internal wheel and their associated sub-issues are in the outer wheel).

Each report can be ascribed more than one Key Issue or sub-issue and so care needs to be taken in interpreting the chart. In this respect, ‘Duty’ and ‘Fatigue’ are often synonymous within individual reports but, collectively, it is telling that these 2 issues continue to represent the bulk of concerns raised to CHIRP by a long margin. Often, we can’t publish these reports or interact with the companies ourselves on specific details due to confidentiality issues but rest assured that CHIRP has represented their content to the CAA to indicate our concerns that it appears to us that some companies are rostering some duties at the top end of the FTL spectrum.

Concern about ‘Pressures/Goals’ is indicative of too much being asked of crews within the resources available (both time and crewing levels). Overt pressure (such as bonus payments for departing on time) or implied pressure (such as leading questions being asked as to the use of Commander’s Discretion) can put crews in an unenviable situation where safety might be compromised as they try to cut corners to satisfy their masters for fear of negative consequences. Companies clearly need to run as efficiently as they can in these uncertain times but, as James Reason pointed out, efficiency and safety can sometimes be in competition with each other and so all of us need to know when to raise the red flag and stop when things appear to be compromising safety. Easier said than done, it sometimes takes real courage to ‘call it’ but those companies with an enlightened ‘Just Culture’ management philosophy will take such calls to heart and step back to review what has been going on. Sometimes it can feel like nothing is resulting from reporting but change will only occur if reports are made rather than keeping it to yourself and grumbling; only with sufficient reporting evidence will company safety management systems respond, and be required to explain what they are doing about it by their regulatory oversight team.

Of the remaining issues, internal communications, relationship management (aka ‘trust’) and company policies /organisation all hint at the same problem. If things are communicated in a transparent and inclusive manner then most people will go the extra mile to achieve the aim. If new policies, procedures or imperatives are not adequately communicated, people feel disconnected from the management, undervalued and disinclined to lean into the task. Middle-management are often blamed for lack of commitment to their subordinate workforces as they try to enact company policies, and they’re often the squeezed layer in the Senior-Middle-Workforce sandwich, but communication (and trust) is a two-way requirement that is not just a transactional process of sending and receiving messages, but also one of interpreting and negotiating meanings – and the meaning you intend is not necessarily the one that the recipient takes away with them. Furthermore, communication and trust is always complicated by an almost infinite number of factors such as expectations, attitude, prejudice, history, values and beliefs, moods, likes and dislikes, etc.

The bottom-line? CHIRP provides a vital safety net as another route to promote change when the normal channels of reporting aren’t delivering results, you don’t feel able to report through company systems, and for collecting reports with safety concerns that did not meet the threshold for normal reporting and would otherwise have gone unwritten. We rely on you to report Human Factors related aviation safety concerns to us so that we can both help in their resolution and highlight relevant issues to others. Reporting is easy by using either our website portal or our App (scan the appropriate QR code shown or search for ‘CHIRP Aviation’ – avoiding the birdsong apps that come up if you just search for CHIRP and the legacy version that we are about to remove!). In our reporting portal you’ll be presented with a series of fields to complete, of which you fill in as much as you feel is relevant – not every field is mandatory, but the more information you can give us the better. Although you’ll need to enter your email address to get access to the portal, none of your details are shared outside CHIRP, and we have our own independent secure database and IT systems to ensure confidentiality.

Steve Forward, Director Aviation

Concerns in relation to engineers’ duty times have been ongoing for a number of years, long before COVID staff shortages. Engineers’ hours are a constant concern for an organisation to balance between excessive overtime, necessity for extending hours for an AOG situation and, worst of all, contract labour – not to mention permanent staff vs contractor ratios in accordance with Part145.A.30(d). Regulation on engineers’ maximum working hours has been looked at before and remained in accordance with the Working Time Directive (WTD) and it’s opt-out concession. It is well-known that shift-work affects our health, our susceptibility to personal injury[1], our performance, and increases the chance of our making mistakes and errors.[2] Fatigue may also be induced by the environment and conditions in which the work is carried out (e.g. noise, humidity, temperature, confined spaces, working overhead).

Recently amended (May 2023), UK Regulation (EU) 1321/2014, Annex II (Part 145) Section A, 145.A.47(b) requires, ‘The planning and organisation of maintenance tasks must take into account human performance limitations, including the threat of fatigue for maintenance personnel during shifts’. The applicable AMC & GM will follow in due course. British Approved organisations need to prepare for compliance by July 2024. EASA AMC1 consolidated[3] Part 145.A.47(b) has the same statement of course, and EASA organisations and British organisations with EASA foreign approvals need to prepare for compliance by December 2024. Your organisation’s Management System 145.A.200, should include a Fatigue Risk Management system (FRMS), defined by ICAO as ‘a data-driven means of continuously monitoring and maintaining fatigue related safety risks, based upon scientific principles and knowledge, as well as operational experience that aims to ensure relevant personnel are performing at adequate levels of alertness’.

We know that night shifts, even shifts with a 04:30 start, have the biggest impact, and rotating shifts are worse than a pattern with the same social start time (for example, 12 hour shifts starting at 08:00). The reality is that engineers’ overtime could be the difference for them buying or not buying a house or having a family holiday for example. Also, contractors working a long way from home like to ‘cane’ the hours so that they can take time at home in blocks rather than five hours alone in digs every evening. Everyone’s personal circumstances are different and, just like pilots, travel distances to work will impact tiredness. A fit and rested engineer staying on after a late shift (a ‘ghoster’), is likely to be more alert than an engineer staying on at work until midday after their fourth nightshift. Working permanent nights can be eased by staying in a “night mode” on odd rest days if family life does not get in the way, not to mention the neighbour’s lawnmower. Training invariably takes place on ‘Days’, so who is looking to remove or reduce a clash between training and returning to shifts? Is it wise for an employer to offer night shift overtime to a day worker, or worse still, the other way around.

The unfortunate outcome of most shift-work patterns is that both the quality and quantity of shift-workers’ sleep suffers. One almost immediate result is fatigue. Of course, not all shift-work is problematic, but severe sleep disturbances may develop over time and lead to chronic fatigue, anxiety, nervousness, and depression, any or all of which frequently demand medical intervention. Such effects are aggravated by working hours that are greater than the typical 35-40 hours per week, which often accompany extended shifts (12 to 16 hours) or multiple job roles e.g. ’moonlighting’. Sleep is the primary human function disrupted by shift-work. Many bodily processes, such as temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate are at their lowest ebb at night so, it is not surprising that people who try to work at night and sleep during the day often report that they cannot do either very well. Shift-workers who need to sleep during the day may have difficulty in falling asleep and remaining asleep because they are attempting to sleep when they are at odds with their circadian rhythms. How long one can continue to do this sort of thing before becoming fatigued is an issue, and of course age[4] is a factor.

There must be organisations around the world with foreign Part145 approvals issued by the UK CAA, British Overseas Territories and EASA, that locally can allow staff to work 96 hours per week (but not in accordance with their Part 145 approval of course). Perhaps we are fortunate for the existing WTD limits to protect our health, and for the fatigue management oversight (and now FRMS) by our Compliance and Safety Departments to protect air safety? In addition, it is vitally important for individuals to consider their personal performance in the best interests of themselves and the task/s in hand, and bring the danger of mismatches and cumulative hours to the attention of their manager. If you suspect you are suffering from fatigue and/or notice performance deteriorating, it is imperative that you find some mitigation and then submit a report using your organisation’s internal reporting vehicle. Needless to say, CHIRP is always ready to accept your Human Factors reports on all the subjects mentioned above.

Phil Young, Engineering Programme Manager

[1] The risk of injury on a night shift is highest at 23:00 but the chance of risks increases as each night is worked. On average, risk is about 13% higher on the second night, more than 25% higher on the third night, and nearly 45% higher on the fourth night shift, than on the first night.

[2] CAA PAPER 2002/06 – Work Hours of Aircraft Maintenance Personnel.

[3] Consolidated, therefore covering Part M, Part 145, Part 66, Part 147, Part T, Part ML, Part CAMO, Part CAO.

[4] Over the age of 45 – 50 years, shift-workers increasingly encounter difficulties in altering their sleep-wake cycles.

This edition’s ILAFFT is taken from our US equivalent organisation’s NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) Callback Newsletter Issue 521 and is a cautionary tale about the need to conduct thorough pre-flight external checks, especially after an aircraft has been undergoing maintenance – ‘remove before flight’ flags are a great aid to spotting things that shouldn’t be there, but the absence of a flag (or a really grubby one that is hiding amongst grease/oil/dirt) isn’t fail-safe and doesn’t necessarily mean that all is well…

Hidden in Plain Sight – an item barely visible was missed on this B777 walkaround inspection and resulted in an expensive air turnback.

After landing at ZZZ, we tail-swapped into an aircraft coming out of the paint shop. We discussed the need for a thorough pre-flight, paying note to the static ports, pitot tubes, etc., and I as FO conducted the exterior and supernumerary area pre-flight. The weather was broken clouds and daylight hours. After take-off, we raised the gear and soon received a GEAR DISAGREE EICAS message due to left main landing gear disagreement. We notified ATC, levelled at 10,000 feet, and maintained airspeed at 250 knots. We completed the non-normal checklist for gear disagree. We contacted Dispatch, and they recommended we return to ZZZ. On [downwind]… we lowered the gear and received a normal gear down indication, landing without incident.

Once parked, Maintenance inspected the left main and found one gear-pin installed without a gear-pin flag attached to it… Maintenance informed us that four of their maintenance team had each conducted individual walkarounds, and none of the four who inspected the aircraft noticed the gear-pin was still installed. Four local Maintenance personnel had inspected the aircraft individually. They annotated in the Airworthiness Release Document (ARD) that they had pulled and stowed all the gear-pins. I, as FO, had walked around the aircraft and did not observe the pin still installed. It appears that there may not have been a gear-pin flag attached to the gear-pin,…making the pin challenging to see. The aircraft came out of a non-Company facility after significant work. All walkarounds require a thorough inspection; however, out of a non-Company city, it’s fair to say extra diligence is required. Additionally,…instead of looking for pins and flags, it would be better to look for an empty gear-pin hole.

Comment No1 – Connected? The lesson to be learned from the recent Air Transport FEEDBACK Edition 146 ILAFFT report when the aircraft began to taxi while ground equipment/personnel were still connected is that the lead member of ground crew or visible equipment should always be in sight of the pilots, with a headset lead of sufficient length, until the all clear signal is given and acknowledged.

CHIRP Response: There are unambiguous safety procedures for confirming whether or not groundcrew or equipment are connected before releasing the parking brake for just this reason. The ILAFFT article acknowledged that and was focused on the fact that the flight crew were tired, under pressure to depart on time, and distracted by receiving new take-off data due to a change in weather conditions so they didn’t follow the procedures. In fact, the PM could see the groundcrew and equipment, it was just that they didn’t do the required check to ensure they were clear.

On an associated topic, we recently discovered that some foreign locations are beginning to use Bluetooth-enabled headsets which provide the groundcrew user with greater freedom to move around the aircraft. There are 2 problems that have surfaced: firstly, the headset wearer may not now always be visible; and, secondly, the kit involves a Bluetooth receiver unit that is plugged into the aircraft instead of the headset itself and there have been incidents where the receiver has not been disconnected before taxying and therefore flight. If operating in foreign locations, crews are advised to check whether these sorts of headsets are in use and, if they are, remind the groundcrew to disconnect the receiver and show it to you when they ‘disconnect’ prior to taxying. We’re unsure as to what process these headsets have undergone in respect of EM compatibility or aircraft manufacturer approval so beware.

STOP PRESS: We recently received the NASA ASRS alert below (ACN 1993903) that directly relates to this problem, it seems that these headsets may be the source of EM problems on some aircraft after all if they are not positioned appropriately when connected up so it’s certainly one to be aware of.

On Day 0, Aircraft X, ZZZ – ZZZZ, was at the gate in ZZZ on APU power, without ground power connected. Just prior to departure, all of our MFDs (Multi‐function Flight Displays) began to flash, then fail, and numerous cockpit lights flashed along with the main cabin lights. We were unable to control the MFDs and until it stopped, the status page had 20+ Faults. This issue caused an 8‐hour delay to clear the faults and replace some components that failed because of it. Both the original FAs (Flight Attendant) and pilots timed out, the flight had to be re‐crewed, and departed late with another aircraft.

When a Maintenance team initially got to the cockpit, they told us that they did not know what caused the problem and proceeded to work on clearing the faults. I explained to the team that clearing the faults was not good enough. I needed to know what caused the problem and that it would not happen in flight. Eventually, the team was joined by another Mechanic who said he knew what caused the problem, because he had seen it about 5 years ago on another 777.

The team returned us to APU power. The Mechanic went down to the nose gear and repeated the light show we saw with the fault. He did this by bringing the headset adapter block nearby the air/ground sensor on the nose gear. Apparently, the sensor works with an electromagnetic field and the headset adapter, when hung too close to it, can trigger the aircraft into “Air Mode.” In our case, in and out of Air Mode rapidly.

How is it even possible that we allow that headset anywhere near a $300 million jet? If we are that foolish, how do we not let every single Mechanic/Ramper/pilot who works with the 777 know that this is a real danger? Perhaps if we explained to the CFO how much this simple error cost air carrier X, he/she would ban that adapter from use on the 777. Oh what a wonderful world that would be.

Comment No2 – CHIRP Clarification We received a complaint from an airline who were concerned that Report No.4 in Air Transport FEEDBACK Edition 146 (FC5223/FC5229 – Punitive and unsafe sickness policy) identified them. They also lodged their displeasure about the nature of the report’s text, and particularly the last sentence which said, “This absolutely highlights the value of reporting; without having done so it is unlikely that anything would have changed until circumstances conspired to bring about a serious incident involving someone who was unfit to operate.” It is not CHIRP’s intention to impugn the reputations of companies and so we are careful to try to disidentify our published material where possible so that those not immediately affected by an issue will not be able to identify the organisation concerned. At the time, we were dealing with similar absence management concerns relating to three companies and were working with the CAA in each of these cases. In reviewing the report text, we don’t believe that the content could be associated with a particular company by the general readership but, as with many of our reports, it is always possible that those with associated detailed knowledge of an issue may be able to identify their company despite the measures we take to disidentify them.

Our article closed with a final paragraph where we lauded the company’s response in changing their policy “…by understanding the dilemma to which it was placing its workforce.” We finished this paragraph with a message intended to highlight the value of reporting in order to enact change. In doing so, we accept that we were somewhat clumsy in our wording. A better wording would have been something like:

“This absolutely highlights the value of reporting; without having done so it is unlikely uncertain that anything would have changed, until and circumstances could have conspired to bring about a serious incident involving someone who was unfit to operate.”

Steve Forward

Former Director Aviation

-

FC5253

–

Incorrect hold entry due to chart confusionIncorrect hold entry due to chart confusionInitial Report

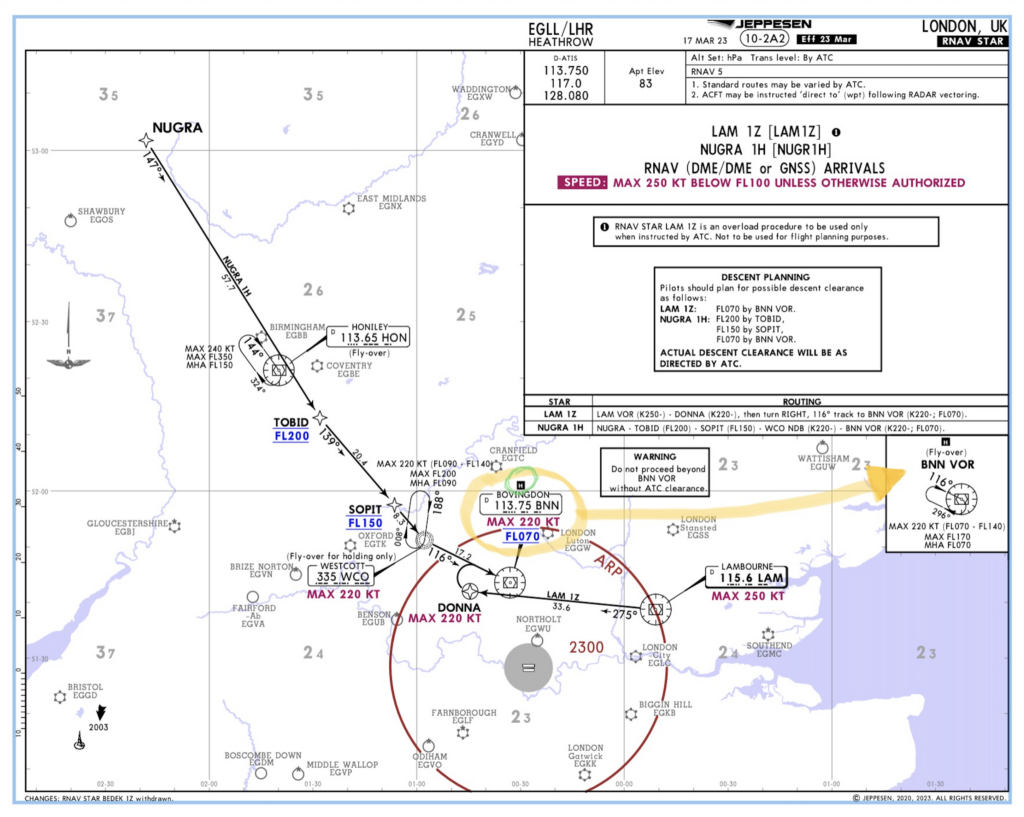

On the descent into EGWU (Northolt) on the NUGRA 1H arrival we were told to expect holding for 10 minutes at Bovingdon (BNN). It was a very high workload phase of flight for us because not only where we constantly being vectored, we were also going in and out of very bumpy rain showers. The instruction given was just a few minutes prior to reaching BNN and was as follows: “Expect holding at BNN, 10-minute delay”.

Right away my co-captain diverted his attention to trying to find the published holding at BNN and showed me the Jeppesen chart for the NUGRA 1H. It was NOT immediately clear what the published holding pattern was. I told him to query approach about what they wanted us to do because we were quickly approaching BNN. I wondered if maybe they wanted us to hold on the missed approach hold from the EGWU ILS25 because it was off a radial from BNN. My co-captain’s query was “Do you want us to hold on the missed approach holding pattern off of BNN?” The reply we got was hold as published. At this point we should have asked for vectors because we couldn’t find the published holding pattern at BNN. Instead, we entered a hold south with 1-minute legs, right hand circuits. Approach asked us if we had entered holding to which we replied yes. They must have realized we entered the wrong hold because the next instructions were vectors for a 10 minute delay.

When we got on the ground, I realized something had gone wrong and opted to call the EGWU Tower to get clarification on the holding. After a few minutes of discussion, I realized my mistake; the Jeppesen Chart had a bubble note indicating published hold for BNN but it was not printed close to point of the hold. Because of the way our charts are displayed in the cockpit you must find the bubble note in a different portion of the screen (slew the view to a different portion of the chart) and it was missed. I asked my co-captain if he had ever seen these notes before on other charts and he had not. Unfortunately, I knew about this subtle change but missed it because of the increasing workload. In the end this was good reminder that if you are unsure of a clearance not to accept it until you are positive you know the instructions. The airspace was very busy but asking for a vector hold would have prevented this incorrect hold entry.

CHIRP Comment

Ordinarily, crews inbound to Northolt do not hold at BNN and are given a vector for the approach so being asked to hold would have been unexpected. Furthermore, the Jeppesen charts for the procedure do indeed have the published hold pattern someway offset from the BNN location on the chart and so there is some sympathy for the crew (see screenshot with highlight arrow). However, as part of their arrival brief, the crew should have made sure they knew what any potential hold procedure would be as they approached BNN and, if not clear what to do when instructed to hold, they should have asked the controller for more information or requested radar vectors. Equally, although controllers were justified in assuming that the pilots would understood what was required when they were issued an instruction and did not query it, the controller could have asked whether the crew knew what was expected of them given that this was not a normal routing. Ultimately, the approach plate gives a warning ‘Do not proceed beyond BNN VOR without ATC clearance’ and so the crew ought to have conducted a self-briefing about what contingencies might result once they arrived at BNN in case they were not cleared to proceed beyond.

-

ATC834

–

Degradation of core safety valuesDegradation of core safety valuesInitial Report

This is going to prove a very difficult issue to articulate as our unit safety performance remains very good and is arguably better than previous years. Unfortunately this is far from the whole picture. Management decisions and a seaming refusal to invest in core systems is simply poking more holes in our Swiss cheese.

Danger Areas

A report following a danger area (DA) infringement many, many years ago highlighted the need to improve our DA notification process and associated radar mapping – it should have resulted in the implementation of a system called LARA [Local And sub-Regional Airspace management support system]. In its infancy, iFacts, our area controlling tool, was supposed to provide conflict support to DA’s. It seems implementation during iFacts was removed due cost and time constraints. LARA was expected and then seemingly parked in favour of our next system DPER [Deployment Point EnRoute]. This was due into AC [Area Control] in 2019 I believe and is significantly over budget and late. It is likely any DA conflict detection may well be missing when and if it is ever deployed. ‘Operational’ date now unknown.

Our Supplementary Information Screen (SIS) is based on 1980/90’s software and is hugely labour intensive to adjust, it is done manually by a human and there are regular mistakes. Attempts have been made to tighten up procedures but there are so many different parties invested from Swanwick Military, Plymouth Military, Qinetic, Swanwick Civil, MABCC or L4M that I’m not sure we have improved things. Over the last three years we have suffered a significant number of danger area infringements for a variety of reasons but ultimately they can be aligned with the problems above. Human error, poor interpretation of information, poor display of information and lack of tools support. As traffic levels return, so will the mistakes I believe. We will only be lucky so many times before a serious incident occurs.

There is no sign of LARA, no sign of the DPER software that’s already overdue, not that the latter would have significantly improved things to the best of my knowledge. Senior NATS management believe it will, but my operational colleagues believe the system is significantly ‘dumber’ than required to improve the current issues. It is an embarrassing mess.

Removal of simulator emergency training.

Over my [numerous] years I have performed [many of] the roles associated with our ART / TRUCE activities. We have improved the range of emergencies trained and also the training of staff behind the scenes who perform pseudo pilot and controller tasks BUT the actual simulator has in my opinion deteriorated year on year. It is, I believe, no longer fit for purpose. We do not resource it appropriately and therefore cannot simulate the full extent of our emergency catalogue and system fall-back scenarios properly. To make matters worse, simulator training has been suspended for the 2023-24 season. All newly valid controllers (of which we now have an increasing number) are expected to undertake simulator ART every year for the first 3 years, I believe this is agreed with the regulator. This year’s suspension is still awaiting regulator sign off I believe but management are pushing ahead regardless of the overwhelmingly negative response they have received from the operational controllers and competency teams.

We learnt a lot from our handling of BA5390 in June 1990 [G-BJRT explosive decompression with commander partially sucked out of cockpit], but we are rapidly undoing all of the good work we did in the years afterwards to improve the standards of our emergency training. The holes in this particular Swiss Cheese are also growing in my opinion and I have grave concerns about our ability to handle a significant event, fortunately they are very, very rare but this probably exacerbates the problem really.

Finally, the operation at Swanwick seems to be being ignored in many other areas, which impacts morale and dictates operational performance to a degree. Our temporary ops room which we should have vacated in 2019 is a disgrace. Trip hazards from worn out carpet tiles, Radar arms that no longer meet DSE rules and regs, a permanently faulty ops room door that impacts our fire and security, inadequate TEMPORARY rest and kitchen facilities. The list goes on but…. the amount of space here limits further explanation.

CHIRP Comment

Notwithstanding the NATS comments above about ongoing expected improvements, the sub-optimal single-point of display of Danger Area information to controllers does not at present appear to be robust enough. CHIRP has previously commented on this following a similar report about Danger Area handling that we received about 2 years ago (ATC820) and that we had hitherto published in our Air Transport FEEDBACK Edition 140 newsletter (Report 4). After considerable correspondence with NATS at the time, we were advised that the LARA tool was unlikely to be fielded until late 2023 and that the NATS senior leadership had commissioned a ‘Feasibility & Options’ paper to identify potential avenues for improved Danger Area information systems that might provide mitigations in the interim. It seems that we are not much further down the road with Danger Area handling and we welcome NATS’ further comments above about “reviewing other alternatives that, whilst not as good as the full DPER integrated solution, may offer an interim step to provide further support to our controllers.”

With regard to emergencies training and the use of the simulator, it has to be acknowledged that the simulator has also to be prioritised for other activities such as airspace changes and system refreshes. As a result, there is undoubtedly a high demand for simulator time, and NATS has to prioritise its use versus the various risks to operations from all of the demands. But, in this respect, it seems that the simulator is under-resourced to a point that, where possible, all courses or mandatory training are being shifted to other means. NATS say they are pro-actively managing simulator use, and, on the face of it, the move from a single simulator day per year to more regular focused simulator and computer-based training sessions may offer some positive opportunities.

Notwithstanding, CHIRP is told that the licensing-requirement days for simulator emergency training[1] have already been shortened due to lack of simulator staff from 4hrs of simulator time and an hour or two in the classroom facilitating discussion of hot topics, to 2hrs of simulator time (shared amongst 4-6 people so approximately 1hr in the hot-seat) and 4 hours in the classroom (normally hosted by a simulator assistant not a competency examiner as was the case in past). Whereas controllers used to run through five to six different emergency scenarios as tactical controllers during these days, now they are likely handling only one or two. Therefore, because the simulator day is now not offered annually to experienced controllers, they may practise only a couple of emergencies every 3 years. CHIRP believes that the reporter’s concerns about the simulator’s fitness for purpose and availability need to be addressed, and it is hoped that this report might be a catalyst for doing so.

Finally, many of these issues and NATS’ responses hint at potential, or at least perceived, sub-optimal communication between the management and the workforce. CHIRP lacks sufficient insight into the NATS internal communications channels to make comment ourselves, but there may be a case for reviewing their efficacy, especially with regard to internal company newsletters or associated electronic channels for example.

[1] A simulator every year after validation until 3 years qualified, then once every 3 years (but able to attend annually in place of the alternative annual recurrent training options if desired).

-

FC5254

–

Altitude deviationAltitude deviationInitial Report

Climbing through FL200 for FL210 with the autopilot engaged, we received an altitude alert indicating that we were 1000’ away from our level off. This was audibly acknowledged in the cockpit by both the PM and PF. At this point it is my belief that there was movement of the speed bug knob or heading bug knob which has a similar tactile feel and appearance as the altitude selector knob in this model of Falcon jet. This resulted in disabling the automatic altitude level-off function of the autopilot; upon realization of the altitude error, immediate corrective action was taken by the PF and a vector was given by ATC.

Apologies were made to ATC for the error. During the post flight debrief we discussed maintaining extra vigilance that the autopilot levels off at the correct altitude and that when changes are made moving flight guidance panel knobs, there is a corresponding indication on the Primary Flight Display.

CHIRP Comment

The fundamental factor in this incident was to remember that in this aircraft type at least, changes to some system settings would disable the automatic level-off function and so great care is required in doing so, especially when close to a critical event such as levelling off. It’s easy in the heat of the moment to mistakenly move the wrong knob so, as the reporter infers, always check that the autopilot is still engaged in the expected mode, and responding, whenever making any changes to parameter settings. -

FC5250

–

Stable Approach Criteria changed without notifying pilotsStable Approach Criteria changed without notifying pilotsInitial Report

At [Airline] we operate using e-manuals which are updated on a daily basis electronically. Periodically we are notified [by notification system] of significant change to operating policy, prior to specific manual upgrades. I attended a recent simulator check and, during the briefing, was informed by the trainer that the Stable Approach Criteria policy had been updated. This was quite a surprise as this is one of the most important elements of our operation, and you would expect this to come via formal notice. The trainer did not know exactly when the change occurred but suggested it was several months ago already. We have now received formal notification of the policy change; however, I know of at least one pilot who unknowingly breached the new policy during this period.

Many of us are concerned at the speed and volume that manual updates occur – the majority of them are small, insignificant and often irrelevant to role. We often only discover policy change through discussions on the flight deck. This also raises the question as to how a change to a fundamental element of our operating policy has slipped through without the chief technical or training pilot deciding / remembering / considering to promulgate formally.

Company CommentFollowing a review of updated IOSA requirements, [Company] made two changes to our Stable Approach Criteria. These were related to ensuring that aircraft were stabilised on the correct lateral profile and that the landing checklist was completed by the 500ft auto-callout. The timing of these changes was immediately before a planned OM-A revision. A decision was made to include this change in the revision, rather than issue a notice making an amendment just days before a new revision was released which then incorporated it. An administrative error led to these two items not featuring in the revision’s list of changes.

When feedback was received that the Stable Approach Criteria appeared to have been changed without notification, the situation was reviewed. At that point, a more significant change to the Stable Approach Criteria was about to be made. This followed standard process and the decision was taken to use this as the vehicle to also highlight the previous modifications. In the Ops Manual Notice (OMN) announcing this change, all modifications were highlighted to ensure pilots were aware of what had previously changed.

This incident led to the documentary update process being reviewed to ensure root cause identified and recurrence prevented.

CHIRP Comment

CHIRP has commented before on the need to have robust policies for a defined cycle of regular changes to documents rather than a series of ad hoc updates. The frequency of such updates depends on the nature of the change (routine, urgent, administrative etc) and, in this case, it seems that rational decisions about how to incorporate the changes were unfortunately derailed by an administrative error that led to them not being properly promulgated. One of the purposes of simulator checks is to refresh crews on recent changes and so this fail-safe activity worked in this case but it is concerning that some crews may have unintentionally been operating in contravention to their OM-A because they weren’t aware of the changes.

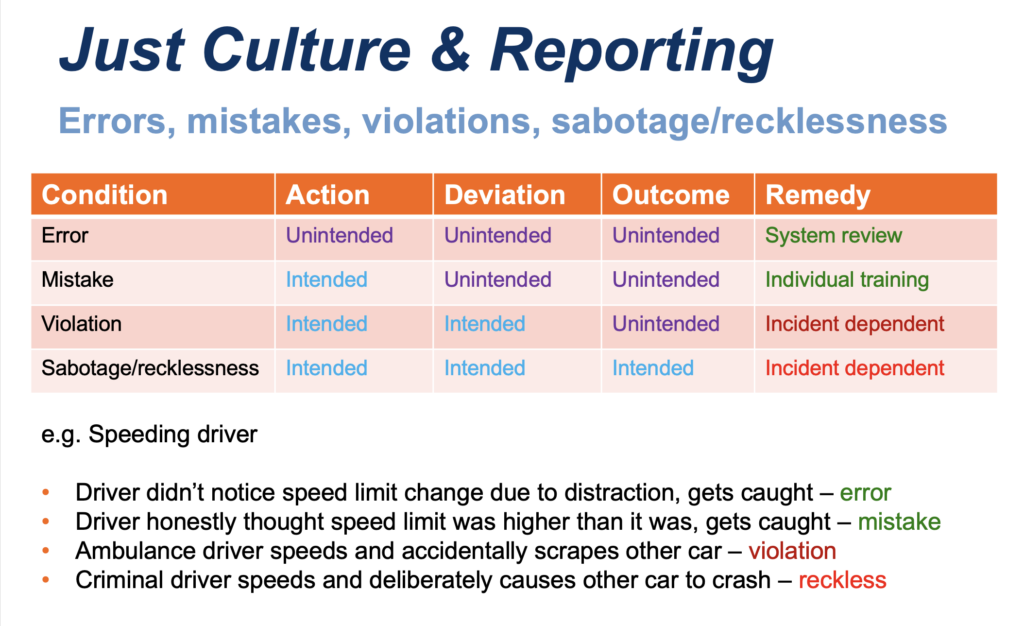

CHIRP is heartened to see that the company is investigating why the administrative error was made, and also why the failure to promulgate was not evident. A change as significant as a revised Stable Approach Policy would hopefully have been considered within the company SMS processes and this should have highlighted the importance of robust promulgation channels. In any such investigations, it’s important to distinguish between errors and mistakes: in ‘Just Culture’ safety terms, ‘mistakes’ are symptomatic of people misunderstanding the task and potentially requiring further guidance or training, whilst ‘errors’ indicate that there are systemic problems that induce people to do the wrong thing. It behoves all organisations to mitigate as many systemic inadequacies as possible so that errors are reduced; in the circumstances of this report, this may identify safeguards that could be introduced to ensure that critical documentation is not lost in the system but properly highlighted to those who use it.

-

FC5240

–

Online learningOnline learningInitial Report

In 2018/9 the company were instructed by the CAA to roster a day of online learning to reflect the time that pilots were spending outside of their duty days completing tech quizzes, pre learning for simulator, aircrew notices etc. Once that happened the company added more study material to be completed before simulator sessions and took the SEP course entirely online (they did roster a day every other year for this item). The required pre reading for the simulator now covers 35 items.

All the courses that I used to attend a classroom to take part in are now done online in our own time and we are rostered a day of every year and a day off every other year to reflect this workload in our own time. At least we were. The company have now taken to rostering the online learning day in chunks, either before or after a duty. They have been challenged by the BALPA, their response is that it complies with the CAA request to record the time we spend doing online learning. My issue with this is that this is a cynical ploy to comply with the CAA requirements ignoring the spirit.

I was rostered an online learning block of 3 hours after an 8 hour duty. I was given 90 minutes to get home and then 3 hours online learning. This fails to take into account the fact that after a total of 9½ hours out of the house, a flight in bad weather at both ends and a commute in bad weather both ways the last thing I feel able to do is sit down and study. In the event I actually contacted crewing and asked them to put me down as fatigued for the online learning part of my duty. Whilst the company may well be complying with CAA requirements, rostering the time in blocks like this either before or after a duty is wholly inappropriate. It is nothing more than a paper exercise to make sure that pilots are available for the maximum number of days flying, over the years the time spent on courses has been pared down to the absolute minimum. A case of the company wanting to have its cake and eat it?

Company CommentShifting to online platforms has allowed us to streamline certain courses and provide more flexibility. The rostered activities, including online learning, are accounted for within the overall duty time but do not directly contribute to FDP calculations. FDP begins at report and concludes when the aircraft becomes stationary after the last sector. Therefore, while online learning may be added to a rostered day, it does not necessarily have to be completed during that specific period. Furthermore, the airline uses a dedicated time allocation for all required courses to ensure the time on roster is adequate. This also explains why the airline uses a different 2 year cycle for the hours allocation.

Lastly, the airline has entirely reviewed SEP training following feedback from our pilots where they felt that the classroom training provided little added value. As a result of this we made some significant improvements to our training delivery. As an example, our fire training now takes place in the simulator (using a simulated fire) in order to provide quality training for our pilots in the environment they are mostly likely to use these skills.

CHIRP Comment

The reporter’s contention is that online learning is now rostered in chunks that are not compatible with other duties. As the company comment notes, such training is not part of FDP calculations and rostering them for a specific duty period is simply a device to ensure that the time spent is accounted for as a duty in its own right and therefore included within basic pay etc as appropriate. Although it was assigned a specific date/time, it did not mean that the training had to be conducted at those times, and the activity could be done during reserve or standby for example, or whenever suited people best. Be that as it may, this was not clear to the reporter (and perhaps others), and so there is a case for the company explicitly stating within its training guidance that the timing of such online training is flexible provided it is completed within a predetermined date as applicable. -

FC5241/FC5251

–

Absence policyAbsence policyInitial Report

FC5241 Report Text: [Company] have released a disciplinary process for pilots reporting sick 3 times in 12 rolling months. I believe this will have a negative impact on the company’s safety. I have already experienced flying with people of weren’t fit to fly but have reported for duty as to avoid disciplinary meetings. This causes great concern for the airlines safety.

FC5251 Report Text: My Company has recently introduced a new Wellness & Absence policy. The policy is draconian and coercive.

Company CommentThe company has received a number of reports regarding the policy which has resulted in changes to the application of the policy. We understand that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be suitable for every situation, and the changes require managers to consider individual circumstances more and exercise discretion accordingly. This aspect is particularly important in the context of aircrew and, for our pilot community, the involvement of base captains and other pilot peers is included to ensure that the responsibilities and obligations of license holders are duly considered. Their expertise and understanding of the unique requirements of flight crew members contribute to a more comprehensive evaluation of each case.CHIRP Comment

Absence management within the airline industry is an issue of topical interest at CHIRP at the moment and we have been engaging with the CAA and a number of airlines in this respect. CHIRP thinks that the issue of flight/cabin crew absence management is something that needs to be reviewed across the industry in order to recognise that crews are in a different situation to those who work outside the aviation world because of the regulatory requirement on individuals not to operate if unfit to fly. As such, we are aware of a UK Flight Safety Committee initiative with the CAA to look at how absence management can be better codified across the aviation community to reflect best-practice. In fact, we majored on this topic in a recent editorial in our Air Transport FEEDBACK Edition 144 Newsletter commenting that the aim should be to produce best-practice protocols that operators can adapt to their own requirements not just for flight/cabin crews but also for other safety-critical staff such as ATC, engineers and others who must not conduct their tasks and should not be induced to work when not fit to operate (be it flying, controlling, engineering etc). -

FC5230

–

Trainer fatigueTrainer fatigueInitial Report

For all training duties on the line it is expected that crews report early. As a Line Training Captain the day must be carefully planned, as you cannot expect support from the trainee. A safe duty requires the trainer to complete Captain, FO and Trainer roles. These duties are rostered as per any other flight duty, 1 hour prior to STD and 30min after landing. As a trainer, the real report is 1:30 before STD, and 1hr after landing which includes debrief. Additional report writing, on average, takes an hour. Each training duty therefore requires an extra 2 hours of duty. I have raised this and have been told it won’t change. There is also resistance from rostering when I do have the energy to change off-duty times. The accumulated fatigue over a year of nearly constant training approaching 900 hours is extreme. A training duty has additional stress from the workload, and to consider these to be “normal flights” is unrealistic. We have had incident reports of tail strikes, and balked landings. I don’t feel the company safety management system of fatigue and rostering is capturing and controlling trainer fatigue. Apart from an internal confidential fatigue report, the only other person contacted was a pilot manager who was not interested.Company CommentOur thanks to the reporter for raising this report to CHIRP. Trainer fatigue is a known industry issue and we are constantly monitoring it proactively and reactively through surveys, predictive and actual fatigue reporting, occurrences and hazard reporting and trend analysis. This is also an issue that is being discussed at FOLG subgroups [Flight Operations Liaison Group – an industry-wide forum for airline operations directors], which we also attend. While there is always scope for improvement, our fatigue management program has recently proven its effectiveness through actions taken on the back of fatigue reports. Crew, trainers included, are encouraged to submit fatigue reports (actual and predictive) should they experience a fatigue related event and/or concern. All our reports are handled confidentially and in accordance with our Just Culture.

While there is no evidence that fatigue has been a factor in any of our safety occurrences happening during a training flight in the past 12 months, our Crew Training team is already working on simplifying the report writing process, which can currently be quite time consuming for our trainers. Other actions are also being discussed and will be communicated to the trainer community once agreed. In the meantime, we would like to reiterate the importance of reporting fatigue related concerns and events through our fatigue reporting program. Reporting allows us to identify issues and trends and in turn enables us to address them. Each report can also be submitted anonymously should the reporter wish to protect their identity even further.

CHIRP Comment

Notwithstanding this report came to us in the post-COVID recovery period when training flights were regular and frequent, the fundamental issue boils down to whether trainers should be given an extra time allowance to accommodate the additional planning and briefing/debriefing training activity. Some companies do allow extra time for the training activity within their reporting/check-in time allowances and it seems to CHIRP that this represents best practice.

More fundamentally, although to some extent the extra burden of training is all part and parcel of being a trainer, in times of increased training flows this can soon mount up and become very challenging; being constantly rostered for frequent training duties can be extremely fatiguing and does not represent best-practice even if additional time is allowed for the training activity. The problem is likely to be seasonal for many companies and so it is vitally important that they monitor the potential for trainer fatigue especially during the Spring/Summer period when increased numbers of training flights are more likely. On a personal level, if as a trainer you feel you are becoming fatigued then do submit fatigue reports to highlight this, multiple if necessary – without data and trend information, safety management systems are unlikely to address issues that may not be apparent to them as endemic rather than just a one-off situation.

Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the concerns that have been raised, I hope the following helps to correct some of the inaccuracies which may be leading to the frustration shown by the individual and may provide useful information to all with regard to ongoing activities in these areas.

Danger Area infringement is recognised as a significant safety issue across our operation with an increased number of safety reports in recent years. The reporters comments regarding delays to the DPER system are accurate, however, development and implementation of LARA continues with ongoing improvements being made to the existing system. In the last 12 months, updates have been made to the radar mapping system used across upper airspace in the London FIR to improve information displayed on tactical displays. Although this does not provide conflict alert, it has improved the information available to controllers to allow them to make better informed decisions on the availability of direct routes and is part of ongoing works to simplify “flexible use airspace” and align procedures across a wide range of external agencies with whom we share these areas. In light of recent changes to the DPER delivery schedule we are in the process of reviewing other alternatives that, whilst not as good as the full DPER integrated solution, may offer an interim step to provide further support to our controllers.

The reporter’s comments relating to the suspension of simulator training for the next year are inaccurate. Simulator training is being provided for both newly valid and experienced controllers as part of their ongoing emergencies training for 2023-24. As per previous years, a range of options are available to controllers to select from. This includes interaction with pilots and simulator sessions for those who wish to participate – it’s not mandatory for all. We’re always looking to make improvements to our simulator capability and would be keen to hear from the reporter directly if they feel there are areas which could be improved further. Their comments relating to improvements to pseudo pilot capability and the range of emergencies which can be simulated are welcomed and we’d welcome any further feedback they may wish to share with us in this area. Alongside this plan for the next year, we continue to evolve how we deliver all elements of training whether licence requirements or not. This will see us expand use of other technology to deliver training more flexibly and effectively and in line with modern learning methods. For our emergency training we are consciously moving away from reliance on a single simulator day once per year to regular drops of more interactive material which becomes more topical and timely and offers a mix of simulator, part task trainer, Computer Based Training and other multimedia systems in line with modern thinking on adult learning techniques.

As with many other companies, access to our sites (and specifically operational areas) was quite rightly limited for a significant period of time between 2020 and 2022. A reduction in the number of people allowed on site and the cancellation of works which weren’t critical to service delivery has meant that planned works in recent years have been reduced and activities are only now starting to “catch-up” with activities that were paused during COVID. The reporter’s comments regarding equipment no longer meeting DSE requirements are a surprise and not something which we recognise; this will be investigated further to ensure any specific concerns which individuals have can be appropriately addressed. We have various routes formally and informally to report and escalate and do not believe this has been raised through any of these. Works have taken place over the last 6 months and a plan is being put in place with our facilities contractor around general replacement and refurbishment of these areas. Although the main door into the Ops room has been out of service for several short periods it was quickly repaired each time and for each event alternative routes used that were both fire and HSE compliant. Having attempted these fixes with the supplier we took the decision that a new door was required and the process put in place to secure a replacement. The nature of the environment means that this needs a bespoke solution meaning long lead times but we expect installation imminently. Works are ongoing across the site as we continue to make improvements for all building users and it’s unfortunate that the reporter doesn’t feel that some of the changes already made have had a more positive effect on their own working environment.

We would welcome the opportunity to discuss any of the issues above directly with the reporter should they wish to do so.