A recent article by Captain Jop Dingemans, an experienced Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) pilot, who posted an on-line article on the website – PILOTS WHO ASK WHY – entitled “10 Lessons I Learned the Hard Way from 7 Years as a HEMS pilot”. The article applies equally well, in most parts, to all types of flying, including commercial fixed wing aviation. We have provided the list below with a short precis of each lesson, but please visit the website to get the benefit of the full version; it is well worth a read.

- Your worst flight could come out of nowhere

- Pilots are very used to routine. Routines are good, SOPs are there for a reason, but what if routines or SOPs don’t quite fit or get interrupted?

- It probably won’t be just one thing that will catch you out. More likely a combination of factors that merge into an ugly monster trying to ruin your day.

- Weather can be your biggest enemy if you let it

- Bad weather does not cause accidents – bad decisions in bad weather do. All pretty basic stuff, and not an issue if we can accurately predict what the weather will be at time X and place Y. The problem is a weather forecast is nothing more than just that, a forecast – not a crystal ball.

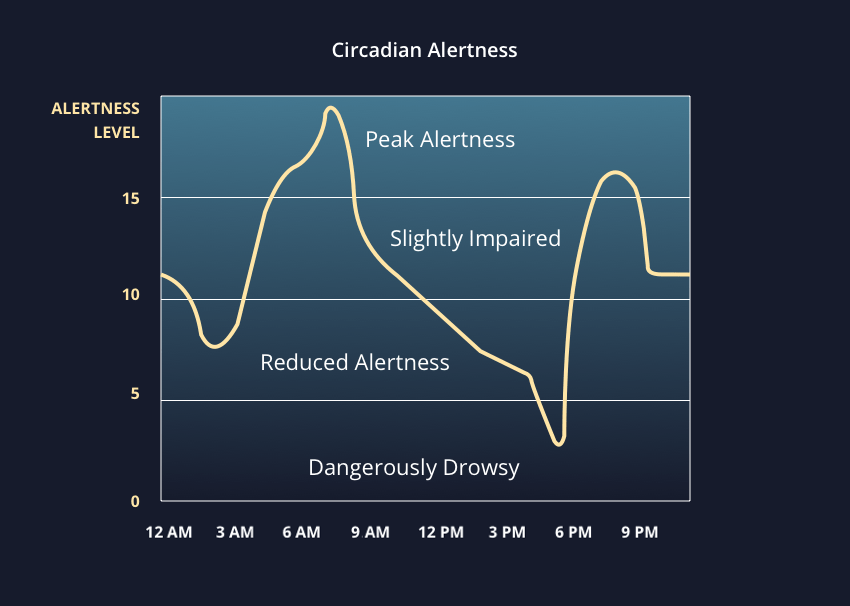

- Fatigue creeps up on you

- I’ve lost count of the number of times my first officer and I have had to correct each other’s actions after a long night. It’s those moments that make me so happy to be involved in a multi-pilot environment: you have each other’s backs when you both need it. We humans are pretty bad at assessing how fatigued we are. It’s like asking a drunk person to accurately state their blood alcohol level.

- The landing site has more threats than the rest of the flight combined

- Taking off from an airport and cruising along to the overhead have less risk than the approach phase. Don’t just take my word for it; the EASA data on this consistently shows the approach phase of HEMS to have the most risk. As the job becomes more ‘routine’ and ‘normal’, normalisation of risk comes in.

- Emotional intelligence matters way more than you think

- Both pilots and management have a tendency to think that being a good pilot means: flying a great ILS approach, flying on the numbers, knowing everything there is the know about the aircraft and any other technical skill imaginable.

- But the longer I am in this job, the more I realise that me and the rest of the crew would rather fly with someone with great emotional intelligence who’s a little rusty on the controls than someone who’s not great to work with but can fly the best ILS you’ve ever seen. It’s more important to understand how other people work and think than trying to be a ‘great’ pilot.

- Life is nuanced, and so is aviation

- Safe vs unsafe, good vs bad, acceptable vs unacceptable: my personal / natural way of looking at things can be quite black and white. Not as effective or helpful as I thought when I entered the industry! People, life, and aviation are nuanced and usually complex, trying to fit it all into two brackets didn’t get me very far – because it doesn’t work. Judgement and risk management are everything.

- Your aircraft will eventually let you down

- After weeks, months and years of no engine failure, you might take that Take-off Decision Point or Landing Decision Point (or V1 for our fixed wing friends) less seriously than someone who has had to deal with it in the heat of the moment. I’ve had a few moments where I’ve been reminded that no matter how great your engineering department is, the aircraft will eventually let you down when you desperately need it not to.

- Thinking the ‘what ifs?’ isn’t neurotic; train yourself to have a healthy dose of vigilance.

- You can’t please everyone, and you shouldn’t try

- There’s pressure from pretty much every angle to deliver. I’ve definitely stepped into the trap in the past and overthought decisions, not because they weren’t safe, but because I didn’t want to let people down. The turning point came when I realised that every time you say “yes” to please someone, you’re gambling with the one thing you’re responsible for: safety.

- You’re not hired to be agreeable. You’re hired to make the right call, even when it disappoints someone, whether that’s your boss or your crew members.

- Trust – but verify

- You can’t have an aviation industry without trust. You trust your crew, your maintenance team, your dispatchers, your medics. Most of the time, that trust is completely reasonable and earned. But over the years, I’ve learnt a critical addition: trust – but verify.

- The job changes you

- I used to fly with an exceptionally experienced (and now retired) HEMS pilot. Anytime he saw people panicking or getting worked up, he’d walk in and jokingly ask: “Is anyone dying, is anyone pregnant? If not, let’s all calm down.” You start this job thinking it’s all about skill, airmanship, decision-making and precision. In some ways it is. What they don’t tell you beforehand though, is that HEMS changes you – slowly and quietly.

- You see people on the worst day of their lives. You land in places no one else would go. You see things you can’t un-see. Some of it stays with you, but also a lot of stuff bothers you less and less as you grow more experienced.

CHIRP thought: this article could be a fitting “springboard’’ to receive comments from our Air Transport readers – what are your 10 lessons, learned the hard way and from your personal experiences in commercial AT aviation? If 10 is too many, how about your top 5? We’d love to hear from you!

Although the Scheme for Regulation of Air Traffic Controllers’ Hours (SRATCOH), previously in Part D of CAP670, is no longer included as a requirement (following publication of ORS 9 Decision 6), it is still available as guidance, and most ANSPs use it. The purpose of SRATCOH is to ensure, so far as is reasonably possible, that controller fatigue does not endanger aircraft and thereby to assist controllers and ANSPs to provide a safe and effective service. The adjustment in regulations allows ANSPs to develop bespoke fatigue risk management systems if they wish. We would expect that any fatigue risk management system would (like SRATCOH did/does) allow for discretionary extension of duties (when a controller is not fatigued) similar to the discretion applied to flight crews. However, current FRM systems in ATC have historically been perceived as somewhat ‘rigid’, with an unjustified assumption that the CAA will take licensing action as a result of each and every any fatigue risk management breach. In reality the CAA reviews every breach report but will only take action where breaches are systemic or excessively repetitive, or where there is an indication that a controller may have continued to provide services whilst fatigued. The CAA recognises that that there will sometimes be circumstances when (for example) extending a duty is a sensible and pragmatic decision provided the controller does not feel fatigued. Example situations include facilitating a landing aircraft that would otherwise need to be diverted, or that was operating on a medical evacuation / organ transfer flight. Provided the event is reported with a clear explanation for the breach and includes reasonable and safe decision making, then the CAA will be sympathetic; licencing action is highly unlikely. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of each individual ATCO not to control when fatigued, but there is always scope for being flexible and adaptable when it is sensible to do so.