FEEDBACK

Top three troubles in the cabin

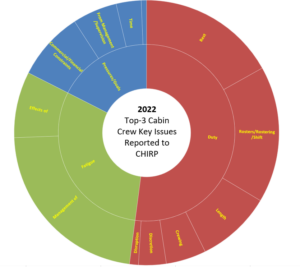

Duty, fatigue and pressures/goals are main issues out of 367 reports

The aviation industry, like many other industries, is still seeing resourcing challenges. Summer schedules were packed with customers making the most of the (almost) unrestricted worldwide travel and cabin crew had to adapt back to busy flying schedules whilst life in general was also getting back into full swing. As a member of cabin crew, it is your responsibility to ensure that you report for duty sufficiently rested and fit (alert) to operate your assigned duty. If you are reporting for a duty, you are stating you are fit to operate; if you don’t feel able to operate or feel unwell, you should not report as fit and should follow company procedures such as speaking to a manager.

CHIRP received 367 confidential cabin crew reports during the last 12 months vs 142 during the same period the year before, 32% of these reports were not reported internally. Reporting internally helps an operator identify trends and mitigate a safety concern that could be occurring. CHIRP are completely independent from the operators, this means that operators do not have access to our reports or data for use during their analysis and identifying specific trends. This is why it is important, if you are comfortable in doing so, that you report your safety concerns to your operator as well as to CHIRP.

Every report that CHIRP receives is triaged and coded, the coding of each report allows for data to be extracted from all of the reports. The top 3 cabin crew key issues reported to CHIRP in 2022 were Duty, Fatigue and Pressures/Goals. These key issues can be further sub-divided into lower level key issues such as those shown in the outer ring of the illustration below.

CHIRP has very robust processes to ensure confidentiality, but we do understand that, for any number of reasons, it may not be an easy decision to submit a report. Once a report has been submitted to CHIRP, we issue a holding response to acknowledge receipt and a formal response is then sent by the most appropriate CHIRP team member. The formal response very often contains specific questions, thereby requiring the reporter to commit more time in order to respond. Sadly, some reporters never reply, it may be that the reporter is just relieved to have got something off their chest, or they simply did not envisage further questions. CHIRP does not contact any other organisations, including your operator, without receiving permission from you, the reporter. Therefore, without responding to our additional questions, reports cannot proceed to a conclusion. This also means that reports cannot be published for the benefit of others and possibly more concerning, could remain a safety issue.

Reports relating to company sickness/absence policies are increasing within CHIRP reporting, with some reporters commenting that they are feeling pressured to operate. Although sickness/absence policies themselves are not a direct safety issue, requirements of the policy may contribute to crew reporting for duty when they are not fit to operate. Other reasons can also be personal pressures to operate, perhaps due to loss of flight pay if a crew member doesn’t fly and so the individual feels that they must fly when not fit to do so. The implications of operating as crew when unfit to do so are clear safety concerns. Noting that safety may be being compromised by crews feeling pressured to operate when they are unfit to do so, whatever the reason for this, CHIRP has highlighted its concerns to the UK Civil Aviation Authority. The UK Flight Safety Committee are leading on a piece of work about attendance management within the industry and the CAA are supporting on that. In addition the CAA are doing some wider work with industry on ‘Fitness to fly’ which we will be able to update on next year. But for now, the important message is that you, as a crew member, must ensure that you only report for duty when fit to do so.

Commander’s Discretion

CHIRP is also seeing an increase in cabin crew reports related to Commander’s Discretion. Commander’s discretion may be used to modify the limits on the maximum daily FDP (basic or with extension due to in-flight rest), duty and rest periods in the case of unforeseen circumstances in flight operations beyond the operator’s control, which start at or after the reporting time.

Regarding the use of discretion, UK Retained Regulations (EU)965/2012 AMC1 ORO.FTL.2059(f) comments on the “…shared responsibility of management, flight and cabin crew…” and that consideration should be taken of “individual conditions of affected crew members…”. Regulation does not state how the Captain should consult their crew or whether this should be conducted face-to-face, individually or as a whole crew.

It is the responsibility of each crew member to know the maximum FDP that they can operate and they should ensure that the Captain is aware if they think they will exceed this. Also, if any members of the crew have been called from standby to operate the duty, this information should be relayed to the Captain because this also might affect whether they can continue the duty into discretion.

When calculating your maximum daily hours, the ‘Flight duty period (FDP)’ means a period that commences when a crew member is required to report for duty, which includes a sector or a series of sectors, and finishes when the aircraft finally comes to rest and the engines are shut down, at the end of the last sector on which the crew member acts as an operating crew member.

This is different to your ‘Duty period’ which means a period which starts when a crew member is required by an operator to report for or to commence a duty and ends when that person is free of all duties, including post-flight duties.

Ultimately, the decision to utilise Commander’s Discretion is not made collectively, it is the Captain who decides whether to use discretion or not, having consulted with all the other crew members to note their personal circumstances, to ensure that the flight can be made safely. The consultation could be via the SCCM and not a separate discussion amongst each crew member.

As with any duty, even if it is ‘legal’ you might still suffer from the effects of tiredness and potentially fatigue. There is a responsibility on each cabin crew member to ensure that should they be suffering from the effects of fatigue, that they report this to their operator.

Jennifer Curran

Cabin Crew Programme Manager

-

CC5883

–

Minimum CrewMinimum CrewInitial Report

I was rostered to position to AAA and then operate back 2 days later, the return flight was scheduled to be on an aircraft with a legal minimum crew of 8.

On the morning of the positioning sector to AAA, the crew list changed numerous times due to sickness and crew being pulled to operate other flights. The aircraft departed with 5 crew positioning plus myself (6 in total).

I was advised that crew from a cancelled flight would be positioned out to join me in AAA and make up my crew.

The following day I received a communication advising me that 1 crew member had been sourced to operate the sector home, this meant we would be operating back in over 30+hrs time with 7 crew. At this point I queried the use of GM1 ORO.CC.205(b)(2) Reduction of the number of cabin crew during ground operations and in unforeseen circumstances as our own operators manual also states “on the day of operation”, this was now 30+hrs in advance.

After my second email questioning the legality of the duty, I never received any further response from the company. My crew list did however update and I operated home with 9 crew (minimum crew +1).

CHIRP Comment

Operators are not permitted to plan a flight with less than the minimum number of required crew. This report highlights the importance of questioning something if you don’t think it is right.

-

CC5886

–

SOPs not being adhered toSOPs not being adhered toInitial Report

Since returning from furlough I’ve witnessed crew not completing pre departure security checks properly. Much of this I believe is due to the SCCM wanting an on-time departure & crew are rushing due to passengers boarding. On occasions passengers have commenced boarding before checks are passed to the SCCM.

For example, on a recent flight, on arrival at the aircraft a crew member proceeded to put their cabin bags into a wardrobe which was full of blankets etc. This particular wardrobe was my check, in my area of responsibility. The cabin crew member was very unhappy that I asked them to remove their bags until I’d checked through & behind the contents of the wardrobe and didn’t seem to understand the importance of me checking the wardrobe pre departure.

On some flights toilet checks have not been actively completed on a regular basis. It’s difficult to ‘prompt’ newer crew to do these checks as they take offence as if they’re being told what to do.

I don’t recall being as worried about safety as I am currently and I feel things are getting worse. It doesn’t help that cabin crew are exhausted at the moment due to terrible rostering.

Sadly, I don’t feel I comfortable reporting my feelings to the company.

Operators CommentThe report highlights several concerns, namely the pre-flight checks and security search, in-flight checks (toilets) and rostering. Completion of the pre-flight checks is an important task performed by each crew member responsible for a section of the cabin prior to the boarding of passengers. This check confirms that the equipment within their area is where it should be and that a security search has been completed. Missing equipment and anything abnormal that is found must be communicated to the Senior Cabin Crew Member (SCCM) and Commander as soon as possible. It is our policy that each crew member shall report any fault, failure, malfunction or defect which the crew member believes may affect the airworthiness or safe operation of an aircraft. The reporter should have raised their concerns on the day to the Commander or SCCM if they felt their colleague was not taking their feedback regarding the conduct of SOPs seriously. It is our policy that crew members report safety occurrences in the safety management system, this includes issues relating to rostering. This allows us to review the data and trends monthly in various meetings attended by colleagues across the business.

There is support available daily to support our crew. We have undergone a huge transformation over the last couple of years, we recognise that some colleagues are familiarising themselves with the working environment and reforming a routine they were once familiar with prior to furlough that resulted in an extended time off work for most of our crew community. We have taken steps to create supportive material available to the crew, and we regularly communicate about safety and the importance of SOPs, feedback, teamwork and communication. Communication is incredibly important on-board and when this does not happen, it’s usually a contributor (as a causal factor) to an incident whether safety related or not. Therefore, we have taken steps to focus our training on the importance of communication with further plans to adopt this into recurrent training in 2023.

The reporter can speak to the cabin crew management team (follow our internal processes) to raise specific concerns and request support. If the reporter feels that they are uncomfortable reporting their feelings or specific feedback or concerns, we also have a confidential reporting service too.

CAA CommentAll flights are required to be operated in accordance with the procedures established in the operations manual, and it is the commander’s responsibility to ensure that all operational procedures and checklists are complied with, this includes pre-flight and post-flight duties, including security checks.

Cabin crew are responsible for completing their assigned duties, and achieving on-time performance is not reason for failure to complete checks. In the first instance, such occurrences should be notified to the commander and reported using the company reporting scheme.

CHIRP Comment

The regulations state (a) The crew member shall be responsible for the proper execution of his/her duties that are:

(1) related to the safety of the aircraft and its occupants; and

(2) specified in the instructions and procedures in the operations manual.

If you are aware that an SOP has not been adhered to, you should feel confident to address this with your colleagues. The more sectors a crew member completes, the more familiar they become with their roles and responsibilities onboard the aircraft, this isn’t just applicable to inexperienced crew, but also to crew that may be on a new aircraft type – we were all new once and must remember to support new crew. It is important that you notify the SCCM if you believe that any checks have not been completed as per your operations manual. Everyone is responsible for ensuring a safe fight, and by not raising concerns before departure you are risking an unsafe situation.

The reporter mentions that they don’t feel comfortable reporting their concerns to their operator, CHIRP is here as a means by which individuals are able to raise safety-related issues of concern without being identified to their peer group, management, or the Regulatory Authority. The fundamental principle underpinning CHIRP is that all reports are treated in absolute confidence in order that reporters’ identities are protected.

CHIRP does not replace organisations’ Safety Management System (SMS) reporting schemes, when these are available and, if they feel able, reporters should always consider using these first before coming to CHIRP because this should result in a faster and more integrated response from the organisation. Most operators also have their own internal confidential report programmes.

-

FC5183(C)

–

Distractions at critical stage of flightDistractions at critical stage of flightInitial Report

The cabin was secured and the cabin crew seated. On finals, the cabin crew called the flight deck with an emergency ‘[alert code]’ chime. The Captain answered and was told a passenger had left their seat and was lying down in the aisle. The cabin was therefore not secure and we cannot land as it is. The Captain agreed and stated we are not landing and will go around.

The First Officer had less than 500 hours and so time was taken to execute the go-around as we prepared ourselves. Cabin crew during the go around were continuously pressing ‘[alert code]’, so much so that it was distracting for the flight deck crew to manage the go-around manually, talk with ATC, change frequencies and avoid a CB [Cumulonimbus thunder-cloud] at the time. The SCCM had to be told during the go-around to stop pressing the intercom buttons. The Captain asked if the passenger was conscious to which the answer was yes so the Captain said he would call back once we had levelled off and it was safe to do so. The First Officer was left with controls and radio in a demanding situation whilst the Captain spoke with the crew to find out the nature of the emergency. The cabin crew said, “I don’t know what to do, I have never done this before.” and was very nervous and panicky on the interphone. Cabin crew managed to seat the passenger who was experiencing a panic attack and motion sickness for landing. Landing was made and medical assistance met us on the stand. More training is required to cabin crew to appreciate the critical stages of flight. More training is also required to deal with medical emergencies and situations in the cabin. The Captain could have kept the controls and asked the first officer to find out what the problem was but, given the severity of the call ‘[alert code]’, it was expected to be something very serious and the Captain wanted to hear first-hand what the event was.

Operators CommentAll crew are trained to deal with inflight events such as go-arounds/missed approaches, medical events and are aware of the critical stages of flight. Two of these events occurring at the same time significantly increases all crew workloads not just of the flight crew. As the medical event occurred shortly before landing when crew are at their stations, the surprise and startle effect could have had a role to play in the cabin crew response. A debrief with all crew at the end of the day will ensure effective communication of issues during the flight and will provide an opportunity for crew to learn from mistakes made during events. Crew are encouraged to report events internally where an additional debrief can take place for the crew involved.

CHIRP Comment

Cabin Crew Advisory Board (CCAB) Comment:

It is unclear from this report exactly why the emergency call/alert was being used excessively. Calm and concise communication is essential and getting accurate information across to other members of the team efficiently and accurately is a must.

As medical incidents do not happen every day this can cause a few moments of uncertainty whilst the situation is assessed and depending on the situation, it may be necessary to expedite landing to ensure the unwell passenger receives the medical care required. Crew members should have an awareness of each other’s workload during the flight, take-off and landing are when the flight crews workload is at its highest. The reported medical incident was taking place with approx. 3 mins to landing, the calls from the cabin, as reported were very distracting. Next time you are onboard, perhaps visit the flight deck at an appropriate time and listen to the sound that the calls from the cabin make, this will give you awareness as they differ amongst aircraft types and may be louder than you think.

Air Transport Advisory Board (ATAB) Comment:

Although it is important not to second-guess the crew because we do not have all of the information and context that may have pertained, go-arounds have their own additional risks and factors that should be carefully considered in such circumstances compared to continuing the approach – there’s an important decision to make about which is the more hazardous, continuing the approach with a potentially sick passenger in an ‘unsecured’ cabin or increasing the workload of both flight crew and cabin crew by going around in marginal conditions? Nevertheless, with regard to the repeated use of the emergency call facility, whilst one would hope that this is covered in training, it may not be apparent to cabin crew what level of distraction this might be causing at critical stages of flight – although they were dealing with two events at once, a medical and a go-around, in the heat of the moment it is important to be disciplined in who is giving alert calls and when.

-

CC5878

–

FatiguedFatiguedInitial Report

I called in fatigued as I have been struggling with sleep, operating busy flights on minimum crew since returning. I didn’t feel better on my days off after resting a lot so I called in fatigued (my previous airline never questioned if I was fatigued or not). Had a phone call with my manager who said it doesn’t sound like ‘aviation fatigue’ so could go down as sick. I don’t think this is fair as she’s not medically qualified to say this. I was fatigued so I don’t see how this can be argued with by a manager. In the future it’s made me less sure about going fatigued if I am fatigued. This shouldn’t be the case and I shouldn’t be made to feel like this. I was very shocked when my manager replied with that. I have worked at another airline for years before and they never said anything like that.

Operators CommentDuring the summer a new process was implemented to initiate wellbeing as it wasn’t being done systematically previously. The process has been refined following feedback and will continue to be monitored to ensure the process is being applied correctly.

CAA CommentUnder UK Retained Regulations (EU) 965/2012 ORO.FTL.110 (b) Operators Responsibilities – the operator must ensure that flight duty periods are planned in a way that enables crew members to remain sufficiently free from fatigue so that they can operate to a satisfactory level of safety under all circumstances.

UK Retained Regulations (EU) Air Ops ORO.FTL.115 Crew Member Responsibilities – the crew member shall not perform duties on an aircraft if he/she knows or suspects they are suffering from fatigue.

Operators are required to have a confidential system in place allowing crew members to report fatigue, and specific non-punitive fatigue reporting processes under their existing safety reporting procedures. There should be a process/procedure in place to ensure feedback to the reporter.

CHIRP Comment

There is a responsibility on each cabin crew member to ensure that should they not be able to perform the duties expected of them, that they report this to their operator. As the effects of fatigue and an individual’s susceptibility to it are not an exact science, it is up to the crew member to decide if they are fatigued or not.

After a crew member reports ‘fatigued’ it is not unusual for an operator to investigate what may have caused this, operators have a responsibility to see if it could have been caused by rostering, rest or something that has happened in a crew members personal life. The most appropriate time to inquire about crew members fatigue is not at the point of reporting fatigued as with the above report, but at a later date where all the facts are available and the crew member is no longer feeling fatigued.

The number of operating cabin crew may be reduced below the regulatory minimum in unforeseen circumstances if the number of passengers carried on the flight is reduced and in accordance with procedures established in the operations manual.

Unforeseen circumstances are defined as incapacitation or unavailability. However, unavailability does not refer to insufficient number of cabin crew, including on standby, owing to absence from work.