FEEDBACK

You report it, we help sort it

Publicising occurrences, serious incidents and accidents is the life-blood of learning for others

As summer rapidly approaches, we’re all no doubt looking forward to what will hopefully be a season of good aviation weather and are dusting off our flying kit and equipment as we prepare to launch into the air. Part of the preparation activity is also to dust off our minds and think again about all those aviation complexities and our ability to deal with them. In the spirit of ‘Prior Preparation Prevents Poor Performance’ what can we learn from our activities last year and also from those who may have been unfortunate enough to have experienced an ‘occurrence’?

The AAIB publications are always an interesting read when it comes to learning from others’ misfortunes (their monthly bulletin is published on the second Thursday of the month and you can receive them by subscribing to AAIB emails). The various association magazines are also a good source of information (too many to name here and I’d risk censure from those I didn’t!), as are the CAA Clued-up and Safety Sense Leaflet publications. The collegiate nature of flying has always been a strong source of tips and advice about traps for the unwary, but the reporting of occurrences, serious incidents and accidents is the life-blood of learning, as is the wide dissemination of associated lessons that might be identified.

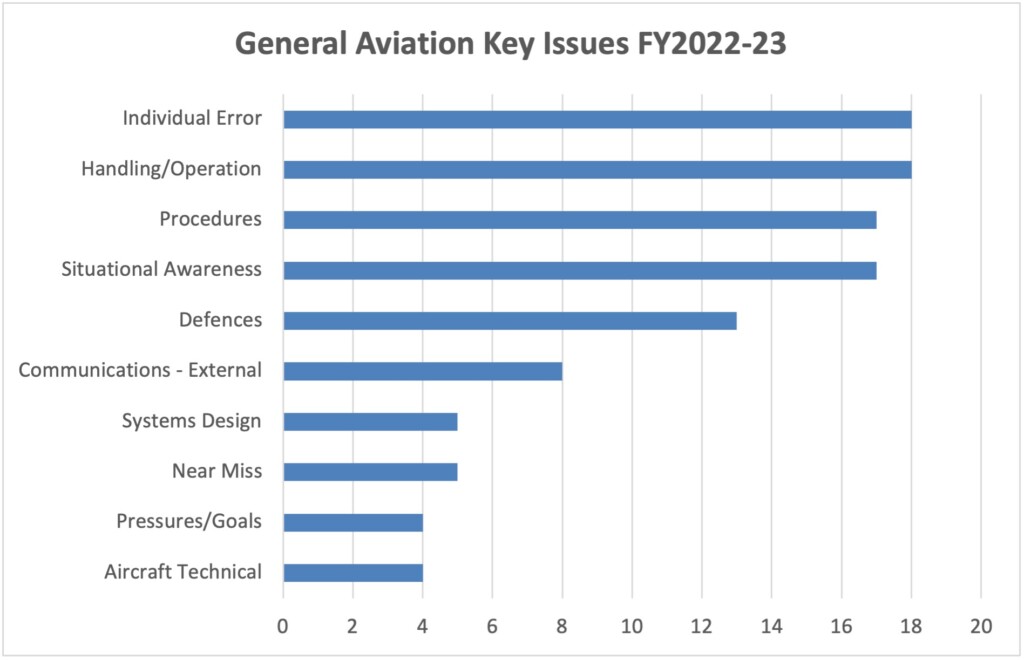

Thankfully, aviation accident rates are extremely low but they have remained relatively constant over the past few decades and a major challenge has been to develop effective processes to identify key causal factors that in some circumstances might lead to an accident, before the accident occurs. One element of this has been to improve the quality of feedback through not just the reporting of incidents but also the reporting of things that nearly happened (but were averted or didn’t develop into a reportable incident) in order to provide additional important information related to contributory causal factors. With aviation being a fundamentally human activity for the most part, some themes recur because we humans are ingenious in our ability to thwart attempts to eliminate errors and mistakes.

Unless things are reported, nothing is likely to change: just moaning in the bar or making anecdotal comments after the event will rarely result in things changing. Modern safety systems recognise ‘Just Culture’ these days, which means you won’t get into trouble for reporting concerns and so we all need to look beyond the ‘what’s in it for me?’ mentality so that issues are passed into and recognised by the ‘system’ (be it local club or more widely). Anyone can submit a report via the ECCAIRS2 Aviation Reporting Portal as the formal route for aviation reporting in UK, and more guidance on the use of the reporting portal is available in CAP 1496. However, although formal reporting systems make an important contribution to the feedback process, they are less successful in gaining information on Human Factors related aspects. Confidential Human Factors reporting systems were introduced to address this. It is important to understand that the confidentiality part applies to the identity of the reporter, not the information; whenever possible the information is disseminated as widely as possible, but in a disidentified manner so that the reporter cannot be recognised, and only with the reporter’s consent.

The UK State Safety Programme acknowledges CHIRP as the UK’s independent confidential voluntary reporting scheme. Broadly speaking, CHIRP provides a vital safety net as another route to promote change when all else fails, and for collecting reports that would otherwise have gone unwritten with associated safety concerns therefore not being reported. Reports generally fall into two broad categories: those indicative of an undesirable trend; and those detailing discrete safety-related events, occurrences or issues. We also often act as an ‘Agony Aunt’ for those who seek our ‘wise’ counsel or just want altruistically to share with others lessons from what may not have been their finest hour. Beyond that, we often provide information and point people to the right sources/contact points for them to resolve their own issues and, depending on the concern and our resource availability, we also champion causes and act as an advocate or the ‘conscience’ of industry and the regulator where we can.

A member of the GA Partnership (GAP) group, CHIRP was recently the subject of their ‘Community in Spotlight’ initiative which highlighted the key elements of our work in the associated CAP2521 information sheet. Essentially, CHIRP operates through the use of four volunteer-based Aviation Advisory Boards comprising members from the principal relevant aviation interests in the UK who provide specialist expertise in the understanding and resolution of issues raised in CHIRP reports.

The four Advisory Boards are titled ‘Air Transport ‘(dealing with all aspects of commercial aviation other than cabin crew), ‘General Aviation’, ‘Cabin Crew’ and ‘Drone/UAS’ (with their associated obvious focus for each). The Advisory Boards are panels of peers who have rigour and credibility as experts in their own right and one of their principal roles is to review reports and issues raised and to provide counsel on the most appropriate way in which specific issues might be resolved. Report information is formally submitted to the Advisory Boards on a confidential basis with all personal details being removed from reports prior to discussion. The Advisory Boards also review the responses received from third-party organisations to assess the adequacy of any action taken in response to a reported concern.

The Advisory Boards are the great strength of the CHIRP process because they provide the breadth and depth of expertise that bestows on us the specialist intellectual horsepower and professional credibility to our work. In addition, the Advisory Boards provide feedback to the CHIRP Trustees on the performance of the Programme.

The bottom line? CHIRP relies on you to report Human Factors related aviation safety concerns to us so that we can both help in their resolution and highlight relevant issues to others. We need your reports! Reporting is easy by using either our website portal or our App (scan the appropriate QR code shown or search for ‘CHIRP Aviation’ – avoiding the birdsong apps that come up if you just search for CHIRP and the legacy version that we are about to remove!). In our reporting portal you’ll be presented with a series of fields to complete, of which you fill in as much as you feel is relevant – not every field is mandatory, but the more information you can give us the better. Although you’ll need to enter your email address to get access to the portal, none of your details are shared outside CHIRP, and we have our own independent secure database and IT systems to ensure confidentiality.

Steve Forward, Director Aviation

NIGHT FRIGHT – A minor distraction with some oil loss and a misbehaving autopilot becomes a crisis when a warning light comes on…

I had been looking forward to the trip for some time. The sortie was from my home airfield in the south-east of England, collecting two people from a local airfield fifteen minutes away and then a day trip to Liverpool to watch a football match. All to be followed by a sunset arrival back at base. My friend was bringing along an acquaintance who was flying for the first time and had agreed to cost-share. Our aircraft, a PA-32R, was fresh out of its fifty-hour check. The autumn morning was crisp and sunny. I had plenty of time to collect my friend and his mate, and even to share a fry-up, as kick off wasn’t until 15.00.

During the pre-flight I noticed a few drips of oil on the nose-wheel. The POH stated a minimum of three quarts, recommended eight and gave a maximum of twelve. The dipstick showed nine. Having owned the aircraft through several annuals and fifty-hour checks I knew that overfilling the oil would lead to some being purged overboard, so I moved on, looking forward to the ‘full English’ awaiting me at my friend’s airfield.

After an uneventful take-off I turned on the autopilot. Like painting the Forth Bridge, keeping the AP serviceable was a never-ending task, the most recent issue being a tendency for it to periodically perform a gentle and un-commanded roll to the right. The problem was still present, so I turned it off and enjoyed hand flying the remainder of the flight, performing my FREDA checks which were all OK.

Following breakfast and an uneventful flight to Liverpool the day got better, with our team winning! Conscious that the departure time would get us home thirty minutes before sunset, we exited the stadium only to find the taxi-rank empty. A little annoying but not a show stopper, as I had my IR(R) and night rating, which was current and, priding myself upon my diligence, had planned for a night approach to both airfields. The passenger was a keen photographer and wanted to get some sunset shots over the Mersey so we didn’t waste any time at the airport. However, there was more oil on the nose-wheel and the dipstick now read 7.5. This confirmed my diagnosis that the oil was overfilled and had purged down to about 8 quarts, which is the normal range. The power check showed the Ts and Ps all OK, confirming that all was well. However, the suction gauge was reading a little lower than usual at 4.9in (4.8 to 5.2 being the normal range according to the POH) but these gauges weren’t always precise and I was perhaps being over-vigilant given the oil situation and the chance of a night arrival.

Take off brought a stunning view of the Mersey just as dusk approached. Settling to a calm but slightly over-cast evening, we made good progress and I was reminding myself how privileged we were to be able to fly like this.

Flying overhead [Airfield] in VFR, now at night, an orange light startled me. It was one of the three annunciator lights I’d tested during every pre-flight but never seen in action for real. Moreover it was very distracting never having seen how bright and out of place it was in a dimmed cockpit, Like the three green landing-gear indicators on the Piper family, these annunciator lights can be swapped over, but they are not truly interchangeable as they have embossed labels. From left to right, they read Oil, Alternator and Vacuum. At night in the dimly lit cabin, it seemed this one, tiny little light – the one marked Oil – was the brightest I’d ever seen.

After the initial clinching of certain body parts, I distilled myself back to basics as a way of figuring out what to do. Ts and Ps all in the green and cross-checked with the EDM700 engine data readout. If we had an oil leak, pressure would fall and temperature would rise, wouldn’t it? I had two contradictory pieces of data – the warning light telling me there’s a problem, but the engine and all other instruments telling me everything was OK. I was only twenty minutes or so from destination. My passenger needed to get home for an evening engagement and was asking what was happening. The next sixty seconds felt like a lifetime, trying to decide what to do, and climbing whilst we had full power available.

We were still below the scattered cloud base and in the climb when the AI toppled. What was going on? What has the oil system got to do with a dry suction system? Back to the checks! The suction gauge was pegged to zero! Yet more confusion…..!

OK enough is enough: between [Airfield] and our home base the only airfields I knew for sure were open were Farnborough and Heathrow. Thankfully, having passed over [Airfield], I knew it was open – though I didn’t have any plates for it. A call to ATC to tell them I was diverting was followed by a 180º turn, resigned to the fact that I’d rather face a taxi ride home than having a cameo role in an AAIB article. Blue lights flashing at the threshold helped me find my way back to the airfield. After this successful diversion a quick check of the oil showed it still at 7.5 quarts. Tired and cold, we headed for the taxi rank, happy that we’d done the sensible thing, but still bemused – what had happened? How could dripping oil, a faulty oil warning light and failed vacuum pump be related? I didn’t believe in coincidences. With the adrenalin still flowing I opened the wiring diagram for the annunciator panel on my friend’s smartphone. What I saw made him smile and made me groan.

What had I learned? A few things actually; I’d self-briefed for a night arrival but hadn’t done adequate planning for the enroute portion – e.g. the airfields to which we might divert. I’d also failed to adjust the radio lights appropriately, being startled by the annunciator light.

The mystery of what went wrong was annoying: the annunciator panel has a vacuum warning light which should have activated if the suction pump had failed (and we know it had, given the suction gauge was pegged to zero and the AI toppled). The annunciator lights in a PA-32 are typically arranged from left to right in the order Vacuum, Alternator and Oil. However the Oil and Vacuum lights in my plane had been transposed!! It was the vacuum that had failed but the oil warning lamp had come on, as it was in the wrong socket. Dripping oil and an oil warning lamp coming on are too much of a coincidence for me to beat myself up about ’confirmation-bias’ but looking at the first diagram in the POH – which detailed the cockpit layout – did show quite clearly the order in which the bulbs should be installed.

Comment No 1 – Speechless?

Regarding GA FEEDBACK Edition 95 Report No.1 (GA1327a) ‘Wrong frequency’. The implementation of the interleaved 8.33kHz channels was bound to cause confusion. Not appreciated by most pilots (who are interested in flying, not radio technology) is that adding 5kHz to a pre-existing 25kHz-plan frequency does not change the frequency (you might want to read that again!). It is actually a means of signifying a narrower channel on the same frequency.

Imagine two pre-existing channels as two houses on a street with a vacant plot between them. Now try to squeeze more into that plot by building two (not just one) new dwellings. You can’t do this unless the new-style houses are narrower than the traditional ones. So with squeezing two new channels between each of the pre-existing ones. A 25kHz channel has more elbow-room to spread out compared to one squeezed into 8.33kHz. The functioning of the radio has to accommodate this. The closer adjacent channels have to be excluded by filtering them out. Transmissions on the new channels must also be restricted so as not to overlap their neighbours. A wide old-style transmission received on a new narrow-bandwidth set could sound distorted, this is not specific to any particular aerodrome.

What should have happened? The “Knowledge” human factor plays a part. Pilots might not understand the spectral bandwidth of the two sidebands of an amplitude-modulated transmission (and with all this jargon, they probably won’t want to try!). However, training should clarify that the 5kHz apparent frequency difference only has the effect of making a transmission compatible with the new equipment. As to the ground station, the operator needs awareness of Speechless Code. When the pilot called in by an unreadable transmission, the ground operator should have said “Station calling [xxx] unreadable, adopt callsign Speechless [One]” followed by pilot’s responses being, principally, one (affirm), two (negative) or three (say again) dashes (sent by keying the mic/PTT, not speaking).

CHIRP Response: There’s still much confusion and unfamiliarity about 8.33kHz radios and probably scope for better education as a result! With regard to an A/G operator just hearing noise on the radio then we agree that the use of the speechless code could potentially be beneficial subject to the usual constraints as to what AG/FISO/ATCO operators are allowed to do with regard to issuing instructions. At least there might be scope for determining who was calling and their intentions if the right set of questions were asked.

For those who may not be familiar with the speechless code, it was conceived as a military procedure used to enable a set of yes/no questions to be asked by ATC when an aircraft had a microphone/voice-transmit problem. The procedure can be initiated by either the pilot or the controller depending on who recognises there’s a problem. If it’s the pilot who realises they have no voice transmission then you initiate the procedure by pressing 4 times on the transmit button to send out 4 long bursts of carrier-wave (4 dashes being morse ‘H’ for ‘Home’). The controller will then make a call along the lines of “Aircraft transmitting on [frequency] adopt the callsign Speechless 1, is this a practice?”. The pilot responds to questions with one long press of the transmit button for ‘yes’, two presses for ‘no’ or 3 presses for ‘say again’. The controller will then pass information or ask yes/no questions depending on the requirement (e.g. “Speechless 1, do you intend to land at [airfield]?, “Speechless 1, [airfield] is using runway [xx], circuit height 1000ft, do you have the airfield in sight?”, “Speechless 1, are you G-ABCD” and so on). If given instructions, pilots use one long transmission (i.e. yes, I’ve done that) to confirm that a requested manoeuvre/action has been carried out (e.g. “Speechless 1, turn left heading 270 and confirm when steady” would result in a long transmission when you were on heading 270). If you have a further emergency then you transmit morse ‘X’ (long, short, short, long) to indicate this and the controller will then go into an additional routine which normally starts with the response “Speechless 1, do you have a further emergency?” and then if you respond ‘yes’, “Speechless 1, can you maintain height?” followed by further questions to find out what your problem is and your intentions as appropriate. Although it’s not regularly used as a civil procedure and so some units may not be familiar with it, airfields could develop standard scenarios and associated yes/no questions pertinent to their operation so that they don’t miss out key things if they decide to use it. See CAP413 Radiotelephony Chapter 10, Para 10.36 for further information.

Comment No 2 – Always treat propellors as live

Thank you for another ‘hi octane’ informative Edition 95 – some ‘been there, almost done that’ revision. Unfortunately, it seems that, notwithstanding training, your warning report in the previous issue but 1 about the dangers of propellors is still risked. Coincidentally I was contemplating CHIRP-ing an incident observed at [Airfield] last week. Many aircraft park on the northern part of the main apron (where the fuel farm is) and this involves a 90º turn, close down and push back. Two pilots and a dog opposite were doing so but, rather than push on the wing, used each blade of the propeller – with a warm engine. My error was not strolling over and in a fellow-pilot, post-flight-friendly-way mention your report/article. Thankfully the proliferation of posed photos of people by props has stopped but the warning needs to be repeated.

CHIRP Response: We can never say it enough, always treat propellors as live – especially with a warm engine. Electrics have been known to be faulty in the past and it doesn’t take much for an engine to fire in such circumstances. In particular, unlike car engines which won’t fire if there’s a break in a cable to the battery, in many aircraft the magnetos are ‘live’ if disconnected and so the engine will fire if the prop is rotated.

Comment No 3 – It’s all a bit hazy

FEEDBACK graphics in Edition 95 were too small and fuzzy to read in the electronic version. They may be pretty, but where is the zoom function?

CHIRP Response: We offer two versions of our FEEDBACK newsletter, pdf (which can be downloaded to your device for reading or printed if desired), and electronic (which require an internet connection to view but can be read in a single-column format on devices with smaller screens). The pdf download versions of documents on the website and app are zoom-able in the normal manner on iPads and browsers etc but the electronic versions have an issue with zooming graphics at the moment which we’re hoping to resolve in a forthcoming update of our app/website. However, our resources are limited and so it’s something that we’re aware of but waiting for our developers to agree a prioritisation amongst some other updates. That being said, some of the graphics we get sent are low-resolution themselves and so we’re often stuck with what we can do anyway. Be assured though, we’re aware of the problem and are on it to try to get it resolved.

-

GA1336

–

Loss of communicationsLoss of communicationsInitial Report

In the cruise under a Traffic Service outside controlled airspace I was approaching the lower edge of the Yorkshire CTA at F100 and I attempted to call ATC to inform them of my position in relation to the airspace. However when I keyed the mike, the radio was overwhelmed with a very loud “squelch” sound which completely drowned out my transmission and meant I could not hear anything from ATC. My first action was to see if this was an external interference but neither of my radios were showing a RX indication. So my next action was to try to cycle the squelch button on the Comm1 radio I was using. This had no effect. So I then tried to switch to Comm2 radio but the situation persisted. I then tried to recycle both Comm radios by turning them off and on again. This again had no effect. So I was about to cycle the transponder to 7600 when I thought to try the ground clearance radio. When I switched on the ground clearance radio the noise vanished and I was able to use Comm1 without any problem but the Comm2 radio was now isolated. I called ATC to inform them of the situation and was informed that they had been trying to call me. They asked me to turn onto 090º which I did. After this I tried turning the ground clearance radio off after 5mins and the problem did not reoccur so I continued to [Airfield]. On the ground at [Airfield] all the radios seemed to be working ok but on doing a system check I got a message “Comm2 requires service”. On an earlier flight I had a problem with the stall-warner heater which on one occasion caused the circuit breakers to pop so I had already decided to have a full electrical check done.

Subsequent information from reporter: I usually use my Comm1 radio for the ongoing communications and use the Comm2 for ATIS frequencies and for ground radio at airports. The Comm2 radio was configured for 8.33KHz the same as my main radio. The issue was with the Comm1 radio. After the incident, and after I had submitted the CHIRP report, I took the aircraft to the engineers to have the radios checked. The issue occurred once again on the way down to the engineers but had again cleared up by the time I arrived. The engineers found that the Comm1 radio was very slightly loose in its mounting cradle and that when vibrated, the connectors at the back came partly unplugged and there was a poor connection/shorting which caused the interference problem. They noticed that pulling and pushing the radio caused it to move forwards and backwards by about 1mm and, when pulled outwards and to the side, the interference manifested itself. They tightened the mounting screw on the unit which made it tight into the sockets and this resolved the problem.

They surmised that some turbulence may have made the radio move in its mount affecting the connector at the back, and this was why the problem came and went. Since they tightened the mounting screw, the problem has not reoccurred.

CHIRP Comment

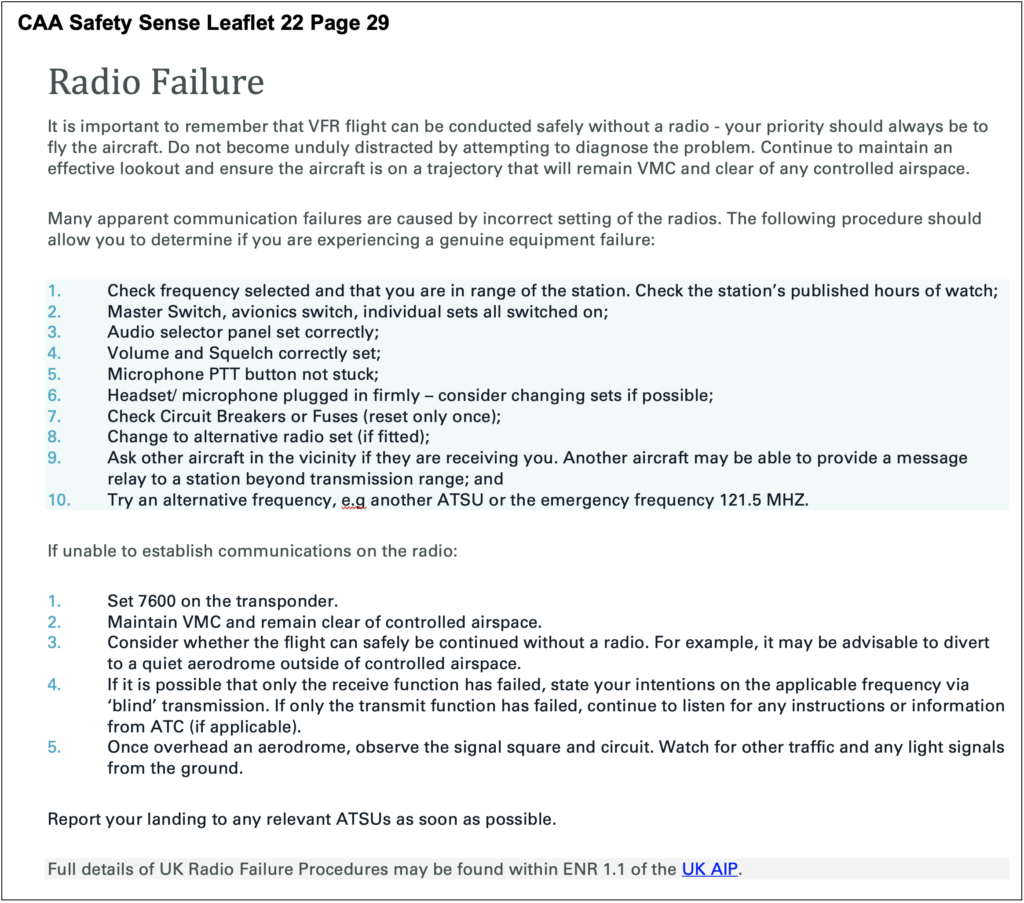

Notwithstanding the mechanical nature of the problem that was eventually traced by the engineers, the possibility of communications failure in flight is something for which we should all be prepared and bears thinking about before we take to the air. Communications problems can manifest themselves from a number of sources including mis-selection of frequencies or modes etc on the pilot’s part, mechanical problems as in this case, or even harmonics between the aircraft’s radios that only manifest themselves at particular frequencies selected (this sometimes occurs, and can be resolved by selecting the out-of-use radio to off). The key thing though is to have a systematic plan for working through the likely issues to try to resolve the problem. In doing so though, don’t forget the maxim ‘Aviate, Navigate, Communicate’ – resolving communication issues should come third in your list of priorities. Consider the use of the 7600 squawk to highlight to ATC that you have a problem, turn promptly away from controlled airspace if relevant and possible so as to avoid an infringement, and make sure you know what you will do if you have to join ‘radio failure’ at your destination airfield.

With regard to diagnosing communication failures, CAA Safety Sense Leaflet 22 (SS22) Page 29 (see below) offers useful advice. In reviewing this advice we note that it doesn’t mention the potential for mis-selection of the radio mode for 8.33/25kHz dual-mode capable radios. We’ve highlighted this to the CAA and suggested that Item 4 in the first list (Volume and Squelch correctly set) could usefully include a prompt to check the mode selector on radios that have a dual 8.33kHz/25kHz capability to make sure it is set correctly.

Key Issues relating to this report

Dirty Dozen Human Factors

The following ‘Dirty Dozen’ Human Factors elements were a key part of the CHIRP discussions about this report and are intended to provide food for thought when considering aspects that might be pertinent in similar circumstances.

Distraction – potential for becoming distracted by loss of communications

Awareness – loss of inputs from other agencies

Knowledge – potentially not being aware of ‘radio failure’ procedures

Communication – inability to communicate with others

This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help. -

GA1339

–

Missed second aircraft on FinalMissed second aircraft on FinalInitial Report

I was taxiing to the hold for take-off, and heard an aircraft call “short final”. I stopped at the hold and waited for an Auster to land. I announced I was lining up on [Runway], moved onto the runway when the Auster was at the bottom end of the runway and waited briefly for it to turn off the runway. As I was rolling to take off, I heard “going around” and around 10 seconds later saw the shadow from an aircraft passing above. The other aircraft (an RV6) called on the radio to say they had called final and I apologised for my error and said I would contact them on landing. I caught up with the RV6 pilot and passenger after the flight and they were very courteous and understanding of my error. The RV6 had flown in with the Auster and said they had seen me waiting at the hold and were then surprised to see me line up on the runway. Luckily they were able to make the decision to go around in plenty of time.

This has not happened to me before, so I am trying to explore the reasons for my error. I have listed what I see as main potential factors, although in hindsight I cannot confirm how significant the contribution was in each case:

Awareness: I missed the 2nd aircraft on approach (it had a white underside with red wing tips). I was also looking into sun (although it was not blinding). Was my scan rusty due to reduced flying over winter? Did I miss the RV6 call final or was it their “short final” call I heard when taxiing and assumed that was the Auster?

Awareness: Ensure I am not biased in my decision and keep an open mind to all possibilities. Just because I heard one call and saw one aircraft does not mean it was the same aircraft and that there was only one aircraft.

Complacency: This was my second flight of the day and the airfield had been quiet for the first one. Did I assume there was only one aircraft and so subconsciously not expect to see another aircraft on my scan? Non-radio is not uncommon at this (my home) airfield so I do not (normally) only rely on radio calls.

Distraction: I was performing a permit check-flight, with a recently rebuilt engine. Was I focused on the flight check and increased risk of engine failure at the expense of airmanship?

CHIRP Comment

By coincidence, in our last edition of FEEDBACK (Edition 95 – February 2023) we had a similar incident (GA1329) where we offered the advice: “…whilst waiting to line up, if possible do so with your aircraft pointing up the final approach/base leg (at an angle appropriate for best visibility depending on the wing configuration of your aircraft) rather than perpendicular pointing at the runway because this will aid your ability to see traffic on the approach”. The reporter in this second report confirmed that in this instance he did have a good view of final approach and base leg but our previous comments stand as good advice for all to consider.

Having formed a mental picture from radio calls, care must be taken not to succumb to Confirmation Bias when looking out thereby only seeing what you expect to see. The reporter makes this point themselves, even though you might think you know what is going on from radio calls, the purpose of looking is to ensure that you really do have all of the information and situational awareness. And when looking up the final approach, think about the potential for other aircraft with different approach angles (e.g. autogyros or para-dropping aircraft on steep approaches) or the possibility of non-radio or radio-failure aircraft that you might not have heard. Some recommend that a turn to position at the runway prior to lining up should always be done in the direction of the circuit pattern because this gives you a chance to see the whole of the circuit before you enter the runway thereby ensuring you have the maximum chance of spotting all other aircraft.

Finally, although not germane to this particular incident, take care when entering the runway to line up whilst you wait for other aircraft to clear. If you do so then you may be denying the runway to other aircraft, especially if you are not prompt in taking off when the runway does become clear: when entering a runway even to just line up you should always be ready and able to take off immediately so that you don’t baulk other aircraft in the circuit.

Key Issues relating to this report

Dirty Dozen Human Factors

The following ‘Dirty Dozen’ Human Factors elements were a key part of the CHIRP discussions about this report and are intended to provide food for thought when considering aspects that might be pertinent in similar circumstances.

Distraction – focusing on the flight ahead (permit check-flight) rather than the task at hand (take-off).

Awareness – did not assimilate that there was a second aircraft on final.

Complacency – relying on radio calls and seeing what was expected rather than thorough lookout.

This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help. -

GA1340

–

Information passingInformation passingInitial Report

On joining the circuit at [Airfield] I was No.2 in the circuit. I heard the first aircraft call downwind and was able to observe it ahead of myself quite easily. I called ‘downwind’ with the reply from ATC of ‘call final’. As I approached base-leg, I observed the other aircraft turn final but there was no final call. ATC at that point cleared a helicopter to fly-taxy onto the runway in use for take-off. I called the ATC to let them know there was an aircraft on approach at which point ATC asked the helicopter to hold. Situational awareness is important and sometimes it can be helpful to others to pass the information on if something is noticed that might cause a problem.

CHIRP Comment

We all have a collective responsibility for safety and, although we don’t know the full story about what was going on in the mind of ATC in this incident, we commend the reporter for their pro-active call to alert them rather than assume that they were aware of the aircraft on final. ‘Rather be thought a fool than not to speak up’, aviation is littered with incidents and accidents that could have been prevented if incurious observers had taken the opportunity to intervene when they thought that things weren’t right but instead kept quiet because they didn’t want to perhaps be seen to make a mistake. In that respect, we should all treat with courtesy those who speak up, even if it turns out to be in error, because an accident might have been prevented in other circumstances.

Key Issues relating to this report

Dirty Dozen Human Factors

The following ‘Dirty Dozen’ Human Factors elements were a key part of the CHIRP discussions about this report and are intended to provide food for thought when considering aspects that might be pertinent in similar circumstances.

Awareness – ensuring the situational awareness of ATC and the helicopter pilot.

Communication – timely passage of information

Teamwork – assisting the effectiveness of ATC.

Assertiveness – decisive contribution

This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help.