The Charity

Aviation

Maritime

DUASxx19

Initial Report

AAIB report 29008 published June 2024. The aircraft was operating at West Wales Airport when the remote pilot observed the engine had stopped. The aircraft had lost all electrical power but continued to fly briefly before disappearing behind a hedge. The aircraft landed a short distance beyond the south-western edge of the airfield. It sustained minor damage; there was no damage to property or injuries to people.

The plan involved the aircraft taking off from West Wales Airfield (WWA), operating in visual line of sight (VLOS) within the air traffic zone (ATZ), and beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) below 3,000ft amsl within 1.8 km of the remote pilot (RP), all within danger area D202D. The RP conducted the take-off at 1215 hrs and handed control of the aircraft to the RP station operator (RPSO).

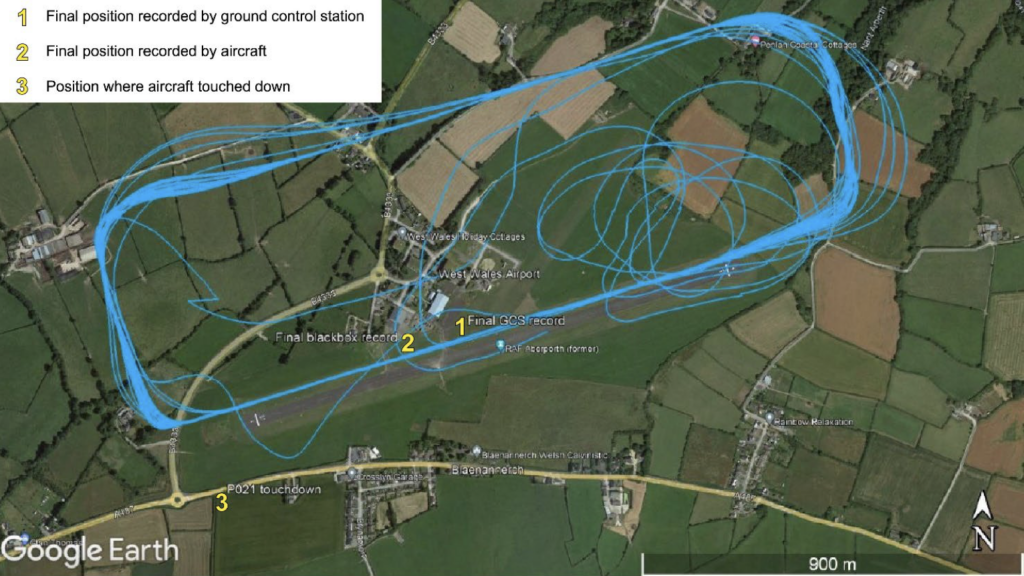

A number of tests were conducted to validate the autopilot and flight control systems. At 1350hrs the RP observed that the engine had stopped, with the aircraft 1,000ft agl over the centre of the airfield and routing along the northern edge of Runway 25. He informed the RPSO that he was taking control by saying “my bird” to which the RPSO acknowledged “your bird”. However, the RP then advised the RPSO that he was not able to gain control; the RPSO then attempted to regain control but without success. The RPSO advised ATC of the situation. Meanwhile, the aircraft continued further along the direction of Runway 25 for about 30secs before turning right and circling, then disappearing from the RP’s sight beyond a hedge (see graphic of the track during the accident flight).

The UAS was a Prion Mk3 fixed-wing monoplane with a 4-stroke petrol engine, which uses an electronic fuel injection system and an electric alternator generator. It has a maximum take-off mass of 55 kg with up to a 4.5 m wingspan and is 3 m in length. The airframe remains visible to the naked eye within a flight envelope of 1,000 m lateral distance up to an altitude of 1,000ft agl.

The Prion MK3 uses ground power prior to engine start. Once the engine has started, power is supplied by an on-board alternator generator. In the event of the generator failing, there is an emergency lithium polymer battery, which will continue to power the systems for a minimum of two hours (calculated at 20°C). This battery is tested for charge before each flight and is continuously charged by the alternator generator while the engine is running. There is a warning system fitted to ensure this battery is connected before flight. The field crew could monitor the charge status of the emergency battery using the flight telemetry system, if selected for display. After flight, the aircraft is connected to ground power, which also charges the emergency battery.

Operator investigation: The operator’s post-flight investigation determined the accident occurred because of the total loss of electrical power. This occurred on the second flight of the day once the emergency battery became discharged, resulting in loss of flight control, communication with both the RP and the RPSO and the shutdown of the engine. Consequently, the aircraft glided to the point it touched down.

The investigation established that the alternator generator system was not delivering power nor charging the emergency battery because of an incorrect wiring connection which had not been identified during assembly. Prior to the accident, the wiring for each airframe was unique. The operator has since standardised the schematics and wiring across the fleet. It also identified that the field crew had not selected the option on the flight telemetry system to enable them to monitor the voltage of the back-up battery.

The investigation also established that the powerplant had been changed the previous day, but that validation of the performance of the alternator generator system had not been carried out. It identified that the fault existed for the first flight of the day which lasted only 35 minutes but which, consequently, did not fully deplete the emergency battery. The fault was not identified prior to the second flight since the emergency battery was charged by the ground power connection prior to flight, preventing the pre-flight check from identifying that the emergency battery charge had been depleted during the first flight.

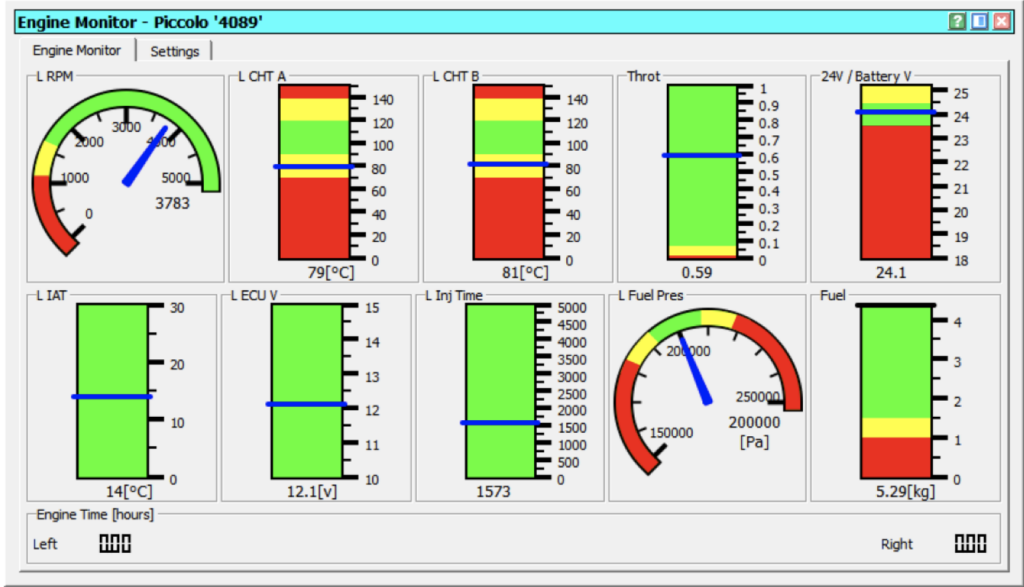

The operator identified that the after-flight check list was missing a check of the emergency battery status prior to the aircraft being connected to the ground power. It also improved the engine monitoring graphical interface flight telemetry system to include voltage indication of the emergency battery to allow its charge status to be monitored in flight (updated engine monitor page shown with new emergency battery voltage indication top right). This would indicate if the alternator generator system was faulty.

CHIRP Comment

Whilst it is easy to see that the emergency battery is charging properly in the second graphic (post the manufacturer’s reconfiguration of the controller display), it is interesting to note that the design of the aircraft originally meant that the wiring layout of each aircraft was unique. This no doubt resulted in quality control of the wiring during manufacture being a difficult and time-consuming process, prone to error.

Given the original controller display design aspect combined with pre- and post-flight emergency battery checks being missing from the list, the holes in the Swiss cheese were lining up perfectly. When the power plant had been replaced the day before the occurrence flight, there appears to have been a functional check of the alternator generator missing from the installation protocol, such that the incorrect wiring was missed.

In summary, the following Human Factor mistakes seem to have all combined to lead to this accident:

- A manufacturing quality control failure to check the functionality of the generator.

- A missing engine change post-installation check that the emergency battery generator was functioning correctly.

- The pilot did not check the generator charge display option or do a pre- and post-flight emergency battery check.