The Charity

Aviation

Maritime

GA1365

Initial Report

Flying just north of [Airfield 1], approx 3,500ft altitude (been flying about 50mins after leaving [Departure Airfield]) in an easterly direction and in communication with [LARS unit]. We were two POB and in excellent VMC. Without any warning an abrupt and excessively noisy engine sound occurred in a staccato (machine-gun-like) repetitive way. I considered a cylinder failure and immediately told [LARS unit]. After communication I confirmed an emergency and declared a PAN – [LARS Unit] said I couldn’t land there, and that nearby [Airfield 1] was not advisable so with altitude still reasonable (lost some power but still had about 80% available I would say) I was vectored to [Airfield 2]. Communicated with their approach who at first asked for a downwind join for [RWY], handed to Tower who then gave me [opposite RWY] for an immediate landing which was far more relevant. Landed without injury or damage to the plane and emergency services were awaiting just off the runway which was comforting. After speaking with my engineer it was thought to be an exhaust problem and next day after removing the top cowling, sure enough the rear port-side cylinder exhaust had come apart at a bottom union. Successfully repaired and plane returned to its destination of [Airfield 2]. ATC and Ops were excellent in both efficiency and attitude in dealing with this incident.

After questions from CHIRP about whether I had thought about potential CO fumes, it never occurred to me that the problem was exhaust related. Given the severity of the noise and its frequency it suggested (to my mind) a more engine-block and mechanical problem. Very briefly the two of us on board got a ‘whiff’ of exhaust fumes but it went as quickly as it came. That didn’t focus my thinking on CO at that point. Nor did it on an engine fire which afterwards became a very real thought. My mind was completely made up and occupied with Aviating, Communicating and getting on the ground in the quickest time. My good height allowed me to descend rapidly and controlling the plane in that process took over my capacity with none to spare. I am not sure how quickly CO would have impaired me, but from the time of my PAN I suspect I was no more than 8 or 9mins flying.

On reflection, I think that, as bizarre as it may seem, had I had some awareness of and experience in hearing ‘rough running’ engine sounds as part of an ‘audio’ training programme for troubleshooting engines and unusual noises you may encounter in mid-air then it may have given me some indication/ awareness of what was going on under the bonnet, its seriousness, and may have given me more pause for thought. Also, given that my mind was so occupied and focused on flying, perhaps a nudge/comment from ATC to check my CO monitor in the cockpit (I have the black-dot type) would have helped and prevented the potential of secondary impact that you refer to. Any subtle prompt from ATC about troubleshooting would have filled the gap I had in that part of my thinking and problem interrogation. Before the incident, and as part of my enroute FREDACO check, I look at the dot to make sure that it hasn’t changed colour with CO. It hadn’t, so there was no prelude or suggestion of a slow deterioration before the final coming apart of the exhaust pipework.

Following on from the incident, I write to advise that once more I had the same occurrence with the exhaust when taking off from [Airfield 3]. I had to declare a PAN and rejoin the circuit to land. On inspection, the exhaust was exactly as it was as previously reported. I haven’t filed any report other than advising you. As an aside [Aircraft Manufacturer] can replace with a new exhaust section (my engineer advises me) but they want £15,000!!! Absurd and unworkable. We are trying to locate a replacement part from America.

CHIRP Comment

The detachment of the exhaust from its mounting would have been a startling event with plenty of noise and understandable uncertainty as to what was going on. Well done to the reporter for their quick decision to request a diversion due to obvious engine-related concerns, and all turned out well in the end. A couple of thoughts occurred to us as from the luxury of our post-event arm-chairs and so we offer them as food for thought.

First, we note the LARS Unit’s comment that the reporter couldn’t land at their location. Whilst we don’t have a detailed knowledge of the exact circumstances, and it may be that there were good reasons for them declining and suggesting an alternative airfield, in circumstances such as these where the engine condition is not known, pilots should think carefully about landing as expeditiously as possible rather than accept being told where to go by ATC. In this respect, it’s important to consider carefully whether a PAN or MAYDAY is the most appropriate call to make. A MAYDAY confers more urgency and an imperative to land at the nearest suitable airfield, which should not be refused. Subject to an airfield having a serviceable landing surface, better to land where you need to following an emergency and then argue the case afterwards than end up with an off-airfield forced landing. Don’t be afraid of using MAYDAY, you will not be admonished afterwards, but you may regret it if you opt just for PAN – a MAYDAY can be easily downgraded to a PAN if subsequent events indicate that urgency is not an issue.

Second, although all ended well at the subsequent diversion, don’t forget that the engine might fail at any point in such circumstances and so make sure you maintain sufficient height to perform a glide approach to the diversion airfield in case the worst happens. The reporter themselves commented that they thought they had a cylinder failure (so a reason in itself for declaring a MAYDAY) which could have resulted in a seized engine at any point if that had been the case; fortunately it was not, but always consider the worst-case scenario.

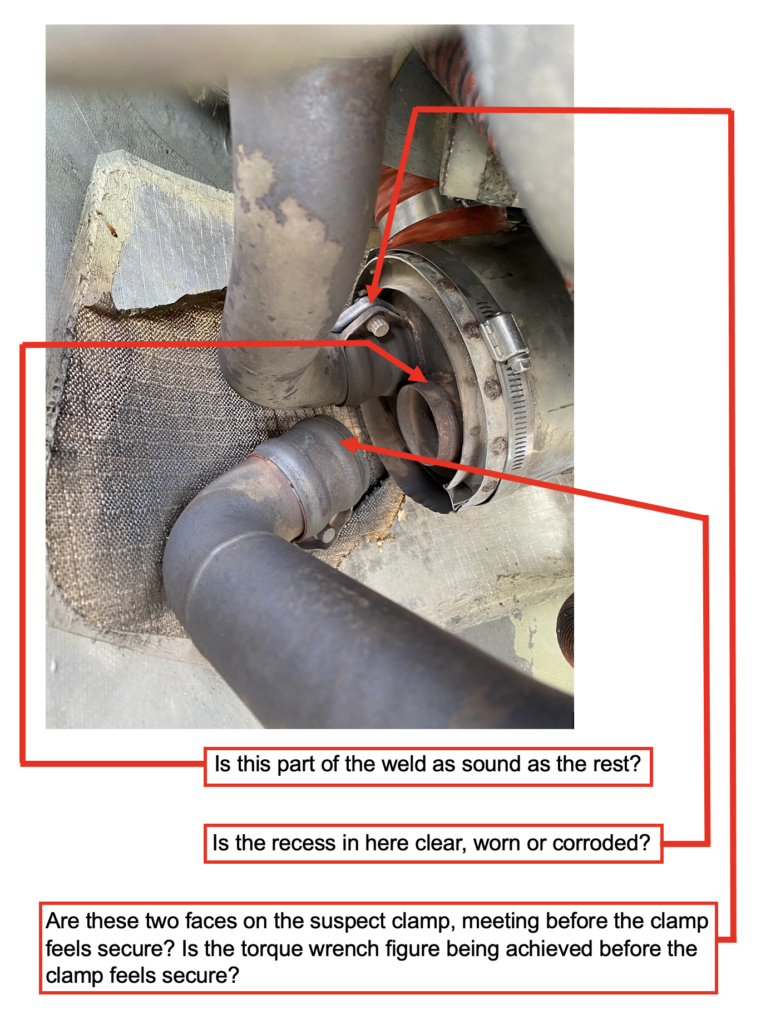

Third, looking at the picture of the exhaust manifold, it looks as if there was some serious heat and potentially flame in the area of the dislodged clamp. The reporter could not know that at the time but there are real dangers of fire in such circumstances and so that’s another reason for declaring a MAYDAY and getting on the ground as soon as possible with an engine or exhaust problem.

Finally, although the reporter didn’t know that the exhaust had separated at the time, loud noises like that with an otherwise functioning engine can be indicative of exhaust problems so do consider whether there may be a risk of CO poisoning as a result. CAA Safety Notice SN-2020/003, the associated Safety Animation, and the CAP2560 Leaflet about CO detectors highlight the importance of having one in the cockpit and, although passive ‘black-spot’ detectors are better than nothing, they do have an expiry date and there are better options available with active electronic versions that can be easily purchased online for relatively little money and have the additional benefit of an aural warning that will hopefully help in attracting attention to the presence of CO depending on cockpit noise levels and any headset active noise reduction if fitted and activated.

The reporter sent us a photograph of the offending manifold after the second separation incident and we passed it to our Engineering Programme Manager for his thoughts. He was cautious about making too many assumptions because he could not see the item in real life and so didn’t know what the pertinent factors were. However, he commented that the manifold connection stub looked quite short and so locating the exhaust properly and securely was vital because any slight movement or vibration would likely cause it to dislodge. In this respect, he wondered whether the clamp might have contaminates on its surfaces that were stopping it closing properly such that the 2 faces of the clamp were meeting before it was secure. He annotated the reporter’s photograph with some thoughts for others to consider during periodic checks of exhaust clamps such as this but we stress that these are generic thoughts rather than being specific comments on the actual installation which we have not seen.

Key Issues relating to this report

Dirty Dozen Human Factors

The following ‘Dirty Dozen’ Human Factors elements were a key part of the CHIRP discussions about this report and are intended to provide food for thought when considering aspects that might be pertinent in similar circumstances.

- Stress – Sudden and alarming engine noises causing tunnelling of focus.

- Pressure – Heightened awareness of the need to get the aircraft on the ground as soon as possible.

- Awareness – Consider all aspects of an engine emergency, including potential forced landing, fire and CO leaks.

- Communication – Consider carefully the value of MAYDAY rather than PAN.

- Assertiveness – Take control of your own circumstances, don’t let ATC or others dictate the outcome.

This data type is not supported! Please contact the author for help.