ENG 771 - Fatigue in engineering

Initial Report

Although fatigue is frequently cited in reports concerning flight crews, I have never encountered an engineer who has formally reported fatigue. Yet, every night shift worker has likely experienced drowsiness or even momentarily fallen asleep while driving home after a shift. Engineers are all too familiar with the foggy mental state and diminished agility that arise when faced with first wave callouts at the end of a night shift. Despite this, we feel compelled to “crack on,” as the principles of human factors do not seem to apply to us in the same way they do to crews. A significant proportion of aircraft maintenance is deliberately scheduled during the early hours of the morning—the time when human performance is most affected by fatigue—simply to maximise aircraft availability for revenue-generating operations. This is not a new practice, but the increasing trend towards shorter turnarounds, often unattended by engineers, has only exacerbated the issue. Maintenance is being concentrated during the small window of time when engineers are at the lowest point in their circadian rhythm. As an industry, we have long ignored human factors, relying instead on processes and procedures to prevent accidents, while neglecting the reality of fatigue for engineers.

comments

Airline Comment

[Airline’s] Engineering & Maintenance (E&M) department actively promotes and builds on the Safety Culture that is the backbone of the airline’s Integrated Management System by cultivating an atmosphere where people can have confidence to report concerns without fear of reprisal, punishment, or blame, and trust that such concerns will be adequately and fairly assessed, by raising awareness and disseminating information, and by learning from mistakes, making necessary changes and adapting to changing demands.

We encourage all personnel to report on any matter but especially those relating to safety concerns with human factors considerations. We promote the use of [Safety System] as the primary platform for incident reporting by engineers employed by [Airline] as well as those employed by contracted maintenance organisations. Human factors are a key consideration in E&M’s processes and procedures. All CAMO, Part 21 and Part 145 personnel receive human factors training every 2 years, regardless of their role, to ensure that staff are aware of the impact that their own actions, or lack thereof, can have on human performance. Our Safety investigators are trained to conduct root cause analyses that look beyond the surface level to be able to link any human factors related concerns with organisational influences, thanks to the use of targeted methodology such as HFACS, Five Why’s, SHELL model, Swiss Cheese. We have also recently launched an operational readiness cycle to evaluate the effectiveness of our fatigue risk management system within E&M.

Since the implementation of SMS within Part 145, there has been even more emphasis on the matter of adequately identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks to our frontline operation and we recognise that most risks are intrinsically linked to the human performance limitations. Our Safety Objectives, as displayed in our MOE, are mostly centred around fostering a safety-oriented mindset amongst maintenance personnel and thus promoting a safety culture where reporting is actively encouraged without fear of reprisal. More specifically, it is one of our Safety Objectives to ensure that all maintenance personnel receive annual recurrent training on human factors and fatigue management. The MOE goes a step further and addresses the consideration of human performance limitations in production planning as well as the monitoring of work accomplishment by management.

CAA Comment

Aviation Safety (Amendment) Regulation 2023 (SI 2023 No. 588) amended UK regulation (EU) No 1321/2014 introduces a Safety Management System (SMS) into Part 145. A SMS relies on a positive reporting culture to ensure its effectiveness. All Part 145 approved organisations should ensure that the reporting of safety concerns including fatigue is encouraged. As a certifying engineer, there is an obligation to ensure that you are fit for duty. The ANO includes overarching safety obligations that require all aviation personnel to act in a manner that does not endanger the safety of an aircraft or its occupants, which would naturally include being fit for duty. In practice, the CAA’s guidance and oversight, along with the SMS requirements under Regulation 1321/2014 (as amended), are the primary mechanisms for enforcing the fitness-for-duty standard for certifying staff.

CHIRP Comment

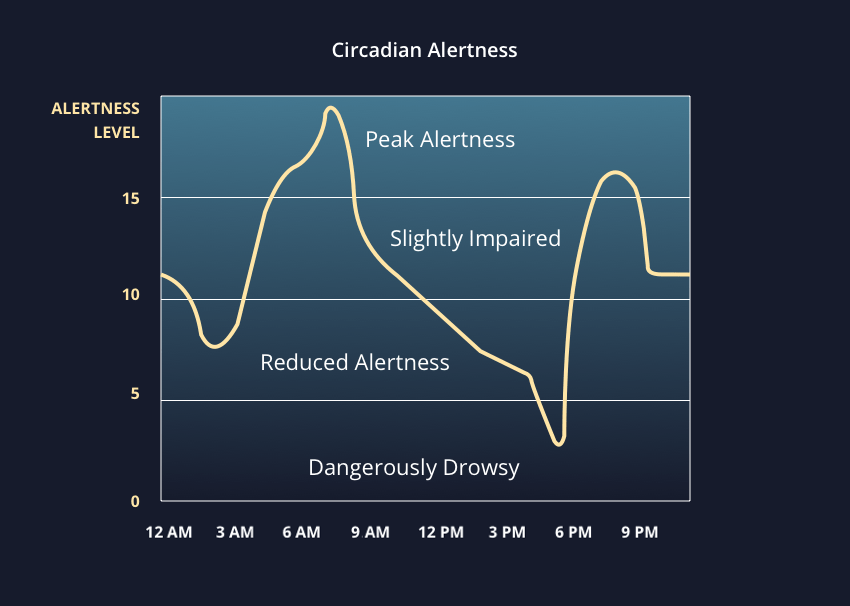

As detailed in the comprehensive CAA comment above, the recently amended regulation now includes human performance aspects for engineers as part of SMS requirements for Part 145 organisations operating in the UK. In addition, the Working Time Directive covers fatigue and tiredness for engineers and all those working in aviation. There is a significant difference between fatigue and tiredness. This distinction is well documented in aviation human factors publications such as Section A, Chapter 11 of CAP737 and SKYbrary’s article on Fatigue. In addition, the HSE article on fatigue offers valuable insights into its effects – especially for shift workers. Engineers should also be aware of the safety aspects of fatigue from their human factors training. The risk is greatest during the body’s natural circadian low, typically between 02:00 and 06:00, known as the Window of Circadian Low (WOCL), when alertness and cognitive function are at their lowest. Engineers often have to work during the WOCL and the very particular pressures that this brings should be a major consideration when rostering engineers for night duties over consecutive nights. In addition, frequent changes to rosters from days to nights are especially challenging. Where possible, individuals should be given enough days on a specific shift to acclimatise and then start performing at an optimal level. CHIRP appreciates that this is not always a practical solution, either for individuals or for maintenance organisations. Nonetheless, rosters should be carefully constructed to accommodate fatigue issues and, where sub-optimal rosters cannot be avoided, companies should have additional defences in place to allow for degradation in human performance.

Fatigue during night shifts can significantly impair judgement, attention and motor skills which are critical faculties for safe aircraft maintenance. The situation is compounded if an engineer hasn’t taken the opportunity or been able to sleep, or sleep well, before the shift. Scientific evidence shows that being awake for 17 hours can impair performance to a level equivalent to a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.05%, and after 24 hours, the effect is similar to a BAC of 0.10%, well above most legal driving limits (Dawson & Reid, 1997). These levels of impairment can lead to missed inspections, incorrect torque settings, or overlooked safety-critical issues.

Typical variation in human alertness across a 24-hour period, illustrating key circadian low points in the early morning and early afternoon.

Adapted from SleepSpace, based on principles of circadian physiology. Source: www.sleepspace.com

The key takeaway is that fatigue-related impairment can be as dangerous as alcohol intoxication yet is often underestimated or invisible in safety-critical work environments. CHIRP would like to challenge maintenance organisations to do more to consider the implications of fatigue in rostering and to highlight the importance of reporting fatigue as a contributory factor to any incidents, when considered relevant.